University of Illinois Urbana-Champaign

| |

Former names | Illinois Industrial University (1867–1885) University of Illinois (1885–1982) University of Illinois at Urbana-Champaign (1982–2021)[1] |

|---|---|

| Motto | "Learning & Labor" |

| Type | Public land-grant research university |

| Established | 1867 |

Parent institution | University of Illinois System |

| Accreditation | HLC |

Academic affiliations | |

| Endowment | $3.38 billion (2023) (system-wide)[2] |

| Budget | $7.7 billion (2023) (system-wide)[3] |

| Chancellor | Robert J. Jones[4] |

| President | Timothy L. Killeen[5] |

| Provost | John Coleman[6] |

Academic staff | 2,548 |

Administrative staff | 7,842[7] |

| Students | 59,238 (2024)[8] |

| Undergraduates | 37,140 (2024)[8] |

| Postgraduates | 20,765 (2024)[8] |

| Location | , Illinois , United States |

| Campus | Small city[10], 6,370 acres (2,578 ha)[9] |

| Newspaper | The Daily Illini |

| Colors | Orange and blue[11] |

| Nickname | Fighting Illini |

Sporting affiliations | NCAA Division I FBS – Big Ten |

| Website | illinois |

| |

The University of Illinois Urbana-Champaign (UIUC, U of I, Illinois, or University of Illinois)[12][13] is a public land-grant research university in the Champaign–Urbana metropolitan area, Illinois, United States. Established in 1867, it is the flagship institution of the University of Illinois system. With over 59,000 students, the University of Illinois is one of the largest public universities by enrollment in the United States.

The university contains 16 schools and colleges[14] and offers more than 150 undergraduate and over 100 graduate programs of study. The university holds 651 buildings on 6,370 acres (2,578 ha)[9] and its annual operating budget in 2016 was over $2 billion.[15] The University of Illinois Urbana-Champaign also operates a Research Park home to innovation centers for over 90 start-up companies and multinational corporations.[16]

The University of Illinois Urbana-Champaign is a member of the Association of American Universities and is classified among "R1: Doctoral Universities – Very high research activity".[17] In fiscal year 2019, research expenditures at Illinois totaled $652 million.[18][16] The campus library system possesses the fourth-largest university library in the United States by holdings.[19] The university also hosts the National Center for Supercomputing Applications.[20]

Illinois athletic teams compete in Division I of the NCAA and are collectively known as the Fighting Illini. They are members of the Big Ten Conference and have won the second-most conference titles. Illinois Fighting Illini football won the Rose Bowl Game in 1947, 1952, 1964 and a total of five national championships. Illinois athletes have won 29 medals in Olympic events. The alumni, faculty members, or researchers of the university include 24 Nobel laureates, 27 Pulitzer Prize winners, two Fields medalists, and two Turing Award winners.

History

[edit]Illinois Industrial University (1867–1885)

[edit]

The University of Illinois, originally named "Illinois Industrial University", was one of the 37 universities created under the first Morrill Land-Grant Act, which provided public land for the creation of agricultural and industrial colleges and universities across the United States. Among several cities, Urbana was selected in 1867 as the site for the new school.[22][23] From the beginning, President John Milton Gregory's desire to establish an institution firmly grounded in the liberal arts tradition was at odds with many state residents and lawmakers who wanted the university to offer classes based solely around "industrial education".[24] The university opened for classes on March 2, 1868, and had two faculty members and 77 students.[25]

The Library, which opened with the school in 1868, started with 1,039 volumes. Subsequently, President Edmund J. James, in a speech to the board of trustees in 1912, proposed to create a research library. It is now one of the world's largest public academic collections.[23][26][27] In 1870, the Mumford House was constructed as a model farmhouse for the school's experimental farm. The Mumford House remains the oldest structure on campus.[28] The original University Hall (1871) was the fourth building built; it stood where the Illini Union stands today.[29]

University of Illinois (1885–1977)

[edit]

In 1885, the Illinois Industrial University officially changed its name to the "University of Illinois", reflecting its agricultural, mechanical, and liberal arts curriculum.[24] According to educational historian Roger L. Geiger, Illinois and a few other public and private universities set the standard for what the research university in the United States would become.[30][31] During his presidency, Edmund J. James (1904–1920) set the policy of building a massive research library.[32] He also laid the foundation for the large Chinese international student population on campus.[33] James established ties with China through the Chinese Minister to the United States Wu Ting-Fang. Class rivalries and Bob Zuppke's winning football teams contributed to campus morale.[23]

Alma Mater, a prominent statue on campus created by alumnus Lorado Taft, was unveiled on June 11, 1929. It was funded from donations by the Alumni Fund and the classes of 1923–1929.[34]

The Great Depression in the United States slowed construction and expansion on the campus. The university replaced the original university hall with Gregory Hall and the Illini Union. After World War II, the university experienced rapid growth. The enrollment doubled and the academic standing improved.[35] This period was also marked by large growth in the Graduate College and increased federal support of scientific and technological research. During the 1950s and 1960s the university experienced the turmoil common on many American campuses. Among these were the water fights of the 1950s and 1960s.[36]

University of Illinois Urbana-Champaign (1977–present)

[edit]

By 1967, the University of Illinois system consisted of a main campus in Champaign-Urbana and two Chicago campuses, Chicago Circle (UICC) and Medical Center (UIMC), and people began using "Urbana-Champaign" or the reverse to refer to the main campus specifically. The university name officially changed to the University of Illinois at Urbana-Champaign by 1977 (although the word "at" was later dropped for marketing purposes by all U of I System campuses by 2021). While this was a reversal of the commonly used designation for the metropolitan area (Champaign-Urbana), a majority of the campus is located in Urbana. The name change established a separate identity for the main campus within the University of Illinois System, which today includes separate institutions at the University of Illinois Chicago (formed by the merger of UICC and UIMC) and University of Illinois Springfield.

In 1998, the Hallene Gateway Plaza was dedicated. The Plaza features the original sandstone portal of University Hall, which was originally the fourth building on campus.[29] In recent years, state support has declined from 4.5% of the state's tax appropriations in 1980 to 2.28% in 2011, a nearly 50% decline.[37] As a result, the university's budget has shifted away from relying on state support with nearly 84% of the budget coming from other sources in 2012.[38]

On March 12, 2015, the Board of Trustees approved the creation of a medical school, the first college created at Urbana-Champaign in 60 years.[39][40][41] The Carle Illinois College of Medicine began classes in 2018.[42]

Philanthropy

[edit]Over the last twenty years state funding for the university has fallen. Private philanthropy increasingly supplements revenue from tuition and state funding, providing about 19% of the annual budget in 2012.[38] Notable among significant donors, alumnus entrepreneur Thomas M. Siebel has committed nearly $150 million to the university, including $36 million to build the Thomas M. Siebel Center for Computer Science, $25 million to build the Siebel Center for Design, and $50 million to support the renamed Department of Computer Science to become Siebel School of Computing and Data Science.[43] Furthermore, the Grainger Foundation (founded by alumnus W. W. Grainger) has contributed more than $300 million to the university over the last half-century,[citation needed] including donations for the construction of the Grainger Engineering Library. Larry Gies and his wife Beth donated $150 million in 2017 to the shortly thereafter renamed Gies College of Business.[44]

Campus

[edit]

The main research and academic facilities are divided almost evenly between the twin cities of Urbana and Champaign, which form part of the Champaign–Urbana metropolitan area. Some parts are in Urbana Township.[45]

Four main quads compose the center of the university and are arranged from north to south. The Beckman Quadrangle and the John Bardeen Quadrangle occupy the center of the Engineering Campus. Boneyard Creek flows through the John Bardeen Quadrangle, parallel to Green Street. The Beckman Quadrangle, named after Arnold Orville Beckman, is primarily composed of research units and laboratories, and features a large solar calendar consisting of an obelisk and several copper fountains. The Main Quadrangle and South Quadrangle follow immediately after the John Bardeen Quad. The former makes up a large part of the Liberal Arts and Sciences portion of the campus, while the latter comprises many of the buildings of the College of Agriculture, Consumer, and Environmental Sciences (ACES) spread across the campus map.[46]

Additionally, the research fields of the College of ACES stretch south from Urbana and Champaign into Savoy and Champaign County. The university also maintains formal gardens and a conference center in nearby Monticello at Allerton Park.

The campus is known for its landscape and architecture, as well as distinctive landmarks.[47] It was identified as one of 50 college or university "works of art" by T.A. Gaines in his book The Campus as a Work of Art.[48] The campus also has a number of buildings and sites on the U.S. National Register of Historic Places including Harker Hall, the Astronomical Observatory, Louise Freer Hall, the Main Library, the Experimental Dairy Farm Historic District, and the Morrow Plots. University of Illinois Willard Airport is one of the few airports owned by an educational institution.[49]

Sustainability

[edit]

In 2008, the University of Illinois Urbana-Champaign became a signatory of the American College and University Presidents' Climate Commitment, binding the campus to the goal of carbon neutrality as soon as possible. In 2010, the first Illinois Climate Action Plan (iCAP) was written to chart a path to this goal. The iCAP is a strategic framework for meeting the university's Climate Leadership Commitments to be carbon-neutral by 2050 or sooner and build resilience with its local community. Since then, the iCAP has been rewritten every five years to track the university's progress.

In December 2013, the University of Illinois launched the Institute for Sustainability, Energy, and Environment (iSEE) on the Urbana-Champaign campus. The institute, under the Vice Chancellor for Research and Innovation, leads an interdisciplinary approach to researching solutions for the world's most pressing sustainability, energy, and environmental needs. In addition, iSEE has engaged students, faculty, staff, and campus leadership in the iCAP process — especially in the areas of zero waste and conservation of energy, food, water, land, and natural resources — as well as sustainability outreach and immersive educational programs.

In her remarks on being named Director of iSEE in 2022, Professor of Agricultural and Consumer Economics Madhu Khanna explained: "We aim to position campus to play a transformative role in moving us all to a more sustainable future."

In 2022, new solar and geothermal energy projects, a reduction in water use, and wide-ranging sustainability research helped the University of Illinois Urbana-Champaign earn its fifth consecutive gold certification in the Sustainability Tracking, Assessment & Rating System (STARS).[50] Illinois has consistently achieved gold certification since it began reporting data through STARS in 2013, and the 2022 score was one of its highest to date.

Currently, the campus features 27 LEED-certified buildings.

Academics

[edit]As of 2024, 87% of students graduate within 8 years of entering, compared to the national median of 58% for all 4-year universities nationwide.[51]

Undergraduate admissions

[edit]| Undergraduate admissions statistics | |

|---|---|

| Admit rate | 43.7% ( |

| Yield rate | 28.0% ( |

| Test scores middle 50%[i] | |

| SAT Total | 1350–1510 (among 40% of FTFs) |

| ACT Composite | 30–34 (among 16% of FTFs) |

| |

The overall first-year admit rate for 2023 is 43.7%,[54] which differ greatly among UIUC colleges — whereas the overall first-choice admit rate is 34.7%, the Grainger College of Engineering has an admit rate of 22.3%. Certain in-demand majors like Computer Science, including Computer Science + X, of which the program being ranked consistently 5th nationwide[55][56] can be extremely competitive, with an acceptance rate of less than 6.8% in 2022, [57] [58] and average freshman ACT composite score of 33.7.[59]

| 2022 | 2021 | 2020 | 2019 | 2018 | 2017 | 2016 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Applicants | 63,257 | 47,593 | 43,473 | 43,509 | 39,406 | 38,965 | 38,093 |

| Admits | 28,354 | 28,395 | 27,520 | 25,684 | 24,496 | 23,974 | 22,881 |

| Admit rate | 44.8 | 59.7 | 63.3 | 59.0 | 62.2 | 61.5 | 60.1 |

| Enrolled | 7,957 | 8,303 | 7,530 | 7,665 | 7,609 | 7,518 | 7,593 |

| Yield rate | 27.4 | 29.2 | 27.4 | 29.8 | 31.1 | 31.4 | 33.2 |

| ACT composite* (out of 36) |

30–34 (55.4%†) |

29–34 (24%†) |

27–33 (50%†) |

27–33 (55%†) |

26–32 (63%†) |

26–32 (85%†) |

26–32 (85%†) |

| SAT composite* (out of 1600) |

1350–1510 (55.4%†) |

1340–1510 (43%†) |

1220–1450 (75%†) |

1230–1460 (79%†) |

1220–1480 (63%†) |

1340–1500 (22%†) |

— |

| * middle 50% range † percentage of first-time freshmen who chose to submit | |||||||

| College | ACT composite* (middle 50%, out of 36) |

SAT composite* (middle 50%, out of 1600) |

Admit rate | Computer Science Programs[54][67] |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Grainger College of Engineering | 33–35 | 1460–1550 | 24.2% | Computer Science admit rate: 7.2% Computer Science + X admit rate: 18.1% |

| College of Liberal Arts & Sciences | 30–34 | 1390–1520 | 41.5% | |

| Gies College of Business | 31–34 | 1400–1500 | 23.1% | |

| School of Information Sciences | 31–35 | 1420–1520 | 55.2% | |

| School of Social Work | 26–30 | 1190–1360 | 50.9% |

In 2009, an investigation by The Chicago Tribune reported that some applicants "received special consideration" for acceptance between 2005 and 2009, despite having sub-par qualifications.[68] This incident became known as the University of Illinois clout scandal.

Academic divisions

[edit]| University of Illinois Urbana-Champaign | |

|---|---|

| College/School | Year Founded

|

| Agriculture, Consumer, and Environmental Sciences | 1867

|

| Fine and Applied Arts | 1867

|

| Grainger College of Engineering | 1868

|

| Medicine | 1882

|

| Information Sciences | 1893

|

| Applied Health Sciences | 1895

|

| Law | 1897

|

| Education | 1905

|

| Liberal Arts and Sciences | 1913

|

| Gies College of Business | 1915

|

| Media | 1927

|

| Social Work | 1944

|

| Aviation | 1946

|

| Labor and Employment Relations | 1946

|

| Veterinary Medicine | 1948

|

| Carle Illinois College of Medicine | 2015

|

The university offers more than 150 undergraduate and 100 graduate and professional programs in over 15 academic units, among several online specializations such as Digital Marketing and an online MBA program launched in January 2016. In 2015, the university announced its expansion to include an engineering-based medical program, which would be the first new college created in Urbana-Champaign in 60 years.[40][41] The university also offers undergraduate students the opportunity for graduation honors. University Honors is an academic distinction awarded to the highest achieving students. To earn the distinction, students must have a cumulative grade point average of a 3.5/4.0 within the academic year of their graduation and rank within the top 3% of their graduating class. Their names are inscribed on a Bronze Tablet that hangs in the Main Library.[69]

Online learning

[edit]In addition to the university's Illinois Online platform, in 2015 the university entered into a partnership with the Silicon Valley educational technology company Coursera to offer a series of master's degrees, certifications, and specialization courses, currently including more than 70 joint learning classes. In August 2015, the Master of Business Administration program was launched through the platform.[70] On March 31, 2016, Coursera announced the launch of the Master of Computer Science in Data Science from the University of Illinois Urbana-Champaign.[71] At the time, the university's computer-science graduate program was ranked fifth in the United States by U.S. News & World Report.[72] On March 29, 2017, the University of Illinois Urbana-Champaign launched their Master's in Accounting (iMSA) program, now called the Master of Science in Accountancy (iMSA) program. The iMSA program is led through live sessions, headed by UIUC faculty.[73]

Similar to the university's on-campus admission policies, the online master's degrees offered by The University of Illinois through Coursera also has admission requirements. All applicants must hold a bachelor's degree, and have earned a 3.0 GPA or higher in the last two years of study. Additionally, all applicants must prove their proficiency in English.[74][75]

The University of Illinois also offers online courses in partnership with Coursera, such as Marketing in a Digital World, which focuses on how digital tools like internet, smartphone and 3D printers are changing the marketing landscape.

Rankings

[edit]

|

|

|

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

In the 2021 U.S. News & World Report "America's Best Colleges" report, UIUC's undergraduate program was ranked tied for 47th among national universities and tied for 15th among public universities, with its undergraduate engineering program ranked tied for 6th in the U.S. among schools whose highest degree is a doctorate.[89]

Washington Monthly ranked UIUC 18th among 389 national universities in the U.S. for 2020, based on its contribution to the public good as measured by social mobility, research, and promoting public service.[90] Kiplinger's Personal Finance rated Illinois 12th in its 2019 list of 174 Best Values in Public Colleges,[91] which "measures academic quality, cost and financial aid."

The Graduate Program in Urban Planning at the College of Fine and Applied Arts was ranked 3rd nationally by Planetizen in 2015.[92] The university was also listed as a "Public Ivy" in The Public Ivies: America's Flagship Public Universities (2001) by Howard and Matthew Greene.[93] The Princeton Review ranked Illinois 1st in its 2016 list of top party schools.[94]

Internationally, UIUC engineering was ranked 13th in the world in 2016 by the Academic Ranking of World Universities (ARWU) and the university 38th in 2019;[95] the university was also ranked 48th globally by the Times Higher Education World University Rankings in 2020 and 75th in the world by the QS World University Rankings for 2020. The Center for World University Rankings (CWUR) has ranked University of Illinois Urbana-Champaign as the 20th best university in the world for 2019–20.[96]

UIUC is also ranked 32nd in the world in Times Higher Education World Reputation Rankings for 2018.[97]

Research

[edit]

The University of Illinois Urbana-Champaign is often regarded as a world-leading magnet for engineering and sciences (both applied and basic).[98]

According to the National Science Foundation, the university spent $625 million on research and development in 2018, ranking it 37th in the nation.[18][16] It is also listed as one of the Top 25 American Research Universities by The Center for Measuring University Performance.[99] Beside annual influx of grants and sponsored projects, the university manages an extensive modern research infrastructure.[100] The university has been a leader in computer based education and hosted the PLATO project, which was a precursor to the internet and resulted in the development of the plasma display. Illinois was a 2nd-generation ARPAnet site in 1971 and was the first institution to license the UNIX operating system from Bell Labs.

National Center for Supercomputing Applications

[edit]The university hosts the National Center for Supercomputing Applications (NCSA), which created Mosaic, the first graphical web browser, the Apache HTTP server, and NCSA Telnet. The Parallel@Illinois program hosts several programs in parallel computing, including the Universal Parallel Computing Research Center. The university contracted with Cray to build the National Science Foundation-funded supercomputer Blue Waters.[101][102][103] The system also has the largest public online storage system in the world with more than 25 petabytes of usable space.[104] The university celebrated January 12, 1997, as the "birthday" of HAL 9000, the fictional supercomputer from the novel and film 2001: A Space Odyssey; in both works, HAL credits "Urbana, Illinois" as his place of operational origin.

Beckman Institute for Advanced Science and Technology

[edit]

The Beckman Institute for Advanced Science and Technology supports interdisciplinary collaborative research in the broad areas of intelligent systems, neuroscience, molecular science and engineering, and biomedical imaging.

Carl R. Woese Institute for Genomic Biology

[edit]The Carl R. Woese Institute for Genomic Biology supports research in genomics and related areas of biology.

Prairie Research Institute

[edit]

The Prairie Research Institute is located on campus and is the home of the Illinois Natural History Survey, Illinois State Geological Survey, Illinois State Water Survey, Illinois Sustainable Technology Center, and the Illinois State Archeological Survey. Researchers at the Prairie Research Institute are engaged in research in agriculture and forestry, biodiversity and ecosystem health, atmospheric resources, climate and associated natural hazards, cultural resources and history of human settlements, disease and public health, emerging pests, fisheries and wildlife, energy and industrial technology, mineral resources, pollution prevention and mitigation, and water resources. The Illinois Natural History Survey collections include crustaceans, reptiles and amphibians, birds, mammals, algae, fungi, and vascular plants, with the insect collection is among the largest in North America. The Illinois State Geological Survey houses the legislatively mandated Illinois Geological Samples Library, a repository for drill-hole samples in Illinois, as well as paleontological collections. ISAS serves as a repository for a large collection of Illinois archaeological artifacts. One of the major collections is from the Cahokia Mounds.[105]

Research Park

[edit]

Located in the southwest part of campus, Research Park opened its first building in 2001 and has grown to encompass 13 buildings. Ninety companies have established roots in research park, employing over 1,400 people. Tenants of the Research Park facilities include prominent Fortune 500 companies Capital One, John Deere, State Farm, Caterpillar, and Yahoo, Inc. Companies also employ about 400 total student interns at any given time throughout the year. The complex is also a center for entrepreneurs, and has over 50 startup companies stationed at its EnterpriseWorks Incubator facility.[106]

In 2011, Urbana, Illinois was named number 11 on Popular Mechanics' "14 Best Startup Cities in America" list, in a large part due to the contributions of Research Park's programs.[107] The park has gained recognition from other notable publications, such as inc.com and Forbes magazine. For the 2011 fiscal year, Research Park produced an economic output of $169.5M for the state of Illinois.[108]

Technology Entrepreneur Center

[edit]The Technology Entrepreneur Center at the University of Illinois Urbana-Champaign is a permanent center established to provide students with resources for their entrepreneurial ideas. The center offers classes, venture and product competitions, and workshops to introduce students to technology innovation and market adoption.[109] Events and programs hosted by the TEC include the Cozad New Venture Challenge, Silicon Valley Entrepreneurship Workshop, Illinois I-Corps, and SocialFuse. The campus-wide Cozad New Venture Challenge has been held annually since 2000. Participants are mentored in the phases of venture creation and attend workshops on idea validation, pitching skills, and customer development. In 2019, teams competed for $250,000 in funding.[110] The Silicon Valley Workshop is a week-long workshop, occurring annually in January. Students visit startups and technology companies in the Silicon Valley and network entrepreneurial alumni from the University of Illinois Urbana-Champaign. Students are exposed to technology entrepreneurship, innovation, and leadership. The trip features corporate leaders, venture capitalists, and entrepreneurs in various stages of a startup lifecycle.[111] Illinois I-Corps teaches National Science Foundation grantees how to learn to identify valuable product opportunities that can emerge from academic research, and gain skills in entrepreneurship through training in customer discovery and guidance from established entrepreneurs.[112] The program is a collaboration between the Technology Entrepreneur Center and EnterpriseWorks, with participation from the Office of Technology Management and IllinoisVentures. The program consists of three workshops over six weeks, where teams work to validate the market size, value propositions, and customer segments of their innovations.[113] SocialFuse is a recurring pitching and networking event where students can pitch ideas, find teammates, and network.[114]

Center for Plasma-Material Interactions

[edit]The Center for Plasma-Material Interactions was established in 2004 by Professor David N. Ruzic to research the complex behavior between ions, electrons, and energetic atoms generated in plasmas and the surfaces of materials. CPMI encompasses fusion plasmas in its research.[115][116][117]

Accolades

[edit]

In Bill Gates' February 24, 2004, talk as part of his Five Campus Tour (Harvard, MIT, Cornell, Carnegie-Mellon and Illinois)[118] titled "Software Breakthroughs: Solving the Toughest Problems in Computer Science," he mentioned Microsoft hires more graduates from the University of Illinois Urbana-Champaign than from any other university in the world.[119] Alumnus William M. Holt, a senior vice-president of Intel, also mentioned in a campus talk on September 27, 2007, entitled "R&D to Deliver Practical Results: Extending Moore's Law"[120] that Intel hires more PhD graduates from the University of Illinois Urbana-Champaign than from any other university in the country.

In 2007, the university-hosted research Institute for Condensed Matter Theory (ICMT) was launched, with the director Paul Goldbart and the chief scientist Anthony Leggett. ICMT is currently located at the Engineering Science Building on campus.

The University Professional and Continuing Education Association (UPCEA), which recognizes excellence in both individual and institutional achievements, has awarded two awards to U of I.[121]

Discoveries and innovation

[edit]Natural sciences

[edit]- BCS theory – John Bardeen, in collaboration with Leon Cooper and his doctoral student John Robert Schrieffer, proposed the standard theory of superconductivity known as the BCS theory. They shared the Nobel Prize in Physics 1972 for their discovery.[122]

- Sweet corn – John Laughnan produced corn with higher-than-normal levels of sugar while he was a professor at the university.[123]

Computer & applied sciences

[edit]- ILLIAC I – Illinois Automatic Computer, a pioneering computer built in 1952 by the University of Illinois, was the first computer built and owned entirely by a US educational institution. Lejaren Hiller, in collaboration with Leonard Issacson, programmed the ILLIAC I computer to generate compositional material for his String Quartet No. 4.[124]

- ILLIAC Suite – is a 1957 composition for string quartet which is generally agreed to be the first score composed by an electronic computer.[125]

- LLVM – compiler infrastructure project (formerly Low Level Virtual Machine). Vikram Adve and Chris Lattner started development as a research assistant and M.Sc. student.[126]

- Mosaic – The first successful consumer web browser was developed at the National Center for Supercomputing Applications[citation needed] at the University of Illinois Urbana-Champaign in 1993.[127]

- NAMD - molecular dynamics simulation code pioneered by Klaus Schulten and colleagues in the Theoretical and Computational Biophysics Group at the Beckman Institute for Advanced Science and Technology.

- PLATO – Programmed Logic for Automatic Teaching Operations[128] was the first generalized computer assisted instruction system. Starting in 1960, it ran on the University of Illinois' ILLIAC I computer. By the late 1970s, it supported several thousand graphics terminals distributed worldwide, running on nearly a dozen different networked mainframe computers. Many modern concepts in multi-user computing were developed on PLATO, including forums, message boards, online testing, e-mail, chat rooms, picture languages, instant messaging, remote screen sharing, and multiplayer video games.[129]

- Touchscreens and Plasma displays – developed by Donald Bitzer in the 1960s.[130]

- Talkomatic[131] is an online chat system[132] that facilitates real-time text communication among a small group of people. Created by Doug Brown and David R. Woolley in 1973 on the PLATO System.[133]

- Synchronized Sound-on-film – Joseph Tykociński-Tykociner publicly demonstrated for the first time a motion picture with a soundtrack optically recorded directly onto the film June 9, 1922.[134]

Companies & entrepreneurship

[edit]UIUC alumni and faculty have founded numerous companies and organizations, some of which are shown below.[135][136][137]

- Andreessen Horowitz, 2009, co-founder Marc Andreessen (BS)

- Advanced Micro Devices (AMD), 1969, co-founder Jerry Sanders (BS)

- Arizona Diamondbacks, 1995, founder, Jerry Colangelo (BA)

- Beckman Coulter, 1935, founder Arnold Orville Beckman (BS, MS)

- BET, 1980, co-founder Robert L. Johnson (BA)

- Chicago Bears, 1920, founder George Halas

- Girls Who Code, 2012, founder Reshma Saujani (BA)

- Harlem Globetrotters, 1926, founder Abe Saperstein

- National Football League, 1920, co-founder George Halas

- Mozilla Corporation, 2005, co-founder Brendan Eich (BS)

- Netscape, 1994, co-founder Marc Andreessen (BS)

- Oracle, 1977, co-founders Larry Ellison (dropout) and Bob Miner (BS)

- Palantir Technologies, 2003, co-founder Nathan Gettings (BS)

- PayPal (Confinity), 1998, co-founders Luke Nosek (BS) and Max Levchin (BS)

- Playboy Enterprises, 1953, founder Hugh Hefner (BA)

- Siebel Systems, 1993, co-founder Thomas Siebel (BA, MS, MBA)

- Tesla, 2003, co-founder Martin Eberhard (BS, MS)

- W. W. Grainger, 1927, founder William Wallace Grainger (BS)

- Wolfram Research, 1987, co-founders Stephen Wolfram and Theodore Gray (BS)

- Yelp, 2004, co-founders Jeremy Stoppelman (BS) and Russel Simmons (BS)

- YouTube, 2005, co-founders Steve Chen (BS) and Jawed Karim (BS)

- Jerry Yue, 2010, founder Brain Technologies, Inc.

Student life

[edit]| Race and ethnicity[138] | Total | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| White | 39% | ||

| Asian | 22% | ||

| Hispanic | 14% | ||

| Foreign national | 14% | ||

| Black | 6% | ||

| Other[a] | 5% | ||

| Economic diversity | |||

| Low-income[b] | 26% | ||

| Affluent[c] | 74% | ||

Student body

[edit]As of spring 2018, the university had 45,813 students.[139] As of 2015[update], over 10,000 students were international students, and of them 5,295 were Mainland Chinese.[140] The university also recruits students from over 100 countries[141][142] among its 32,878[143] undergraduate students and 10,245[143] graduate and professional students.[142] The gender breakdown is 55% men, 45% women.[142] UIUC in 2014 enrolled 4,898 students from China, more than any other American university. They comprise the largest group of international students on the campus, followed by South Korea (1,268 in fall 2014) and India (1,167). Graduate enrollment of Chinese students at UIUC has grown from 649 in 2000 to 1,973 in 2014.[144]

Student organizations

[edit]

The university has over 1,000 active registered student organizations,[145] showcased at the start of each academic year during Illinois's "Quad Day." Registration and support is provided by the Student Programs & Activities Office, an administrative arm established in pursuit of the larger social, intellectual, and educative goals of the Illini Student Union. The Office's mission is to "enhance ... classroom education," "meet the needs and desires of the campus community," and "prepare students to be contributing and humane citizens."[146] Beyond student organizations, The Daily Illini is a student-run newspaper that has been published for the community of since 1871. The paper is published by Illini Media Company, a not-for-profit which also prints other publications, and operates WPGU 107.1 FM, a student-run commercial radio station. The Varsity Men's Glee Club is an all-male choir at the University of Illinois that was founded in 1886.[147] The Varsity Men's Glee Club[148] is one of the oldest glee clubs in the United States as well as the oldest registered student organization at the University of Illinois. As of 2018, the university also has the largest chapter of Alpha Phi Omega with over 340 active members.[149]

Greek life

[edit]There are 59 fraternities and 38 sororities on campus.[150] Of the approximately 30,366 undergraduates, 3,463 are members of sororities and 3,674 are members of fraternities.[151] The Greek system at the University of Illinois Urbana-Champaign has a system of self-government. While staff advisors and directors manage certain aspects of the Greek community, most of the day-to-day operations of the Greek community are governed by the Interfraternity Council and Panhellenic Council.[152] A smaller minority of fraternities and sororities fall under the jurisdiction of the Black Greek Council and United Greek Council; the Black Greek Council serves historically black Greek organizations while the United Greek council comprises other multicultural organizations.[153][154] Many of the fraternity and sorority houses on campus are on the National Register of Historic Places.

Student government

[edit]

U of I has an extensive history of past student governments. Two years after the university opened in 1868, John Milton Gregory and a group of students created a constitution for a student government. Their governance expanded to the entire university in 1873, having a legislative, executive, and judicial branch. For a period of time, this government had the ability to discipline students. In 1883, however, due to a combination of events from Gregory's resignation to student-faculty infighting, the government formally dissolved itself via plebiscite.[155]

It was not until 1934, when the Student Senate, the next university-wide student government, was created. A year before, future U of I Dean of Students, Fred H. Turner and the university's Senate Committee on Student Affairs gave increased power to the Student Council, an organization primarily known for organizing dances. A year after, the Student Council created a constitution and became the Student Senate, under the oversight of the Committee on Student Affairs. This Student Senate would last for 35 years.[156] The Student Senate changed its purpose and name in 1969, when it became the Undergraduate Student Association (UGSA). It ceased being a representational government, becoming a collective bargaining agency instead. It often worked with the Graduate Student Association to work on various projects[157]

In 1967, Bruce A. Morrison and other U of I graduate founded the Graduate Student Association (GSA). GSA would last until 1978, when it merged with the UGSA to form the Champaign-Urbana Student Association (CUSA).[158][159] CUSA lasted for only two years when it was replaced by the Student Government Association (SGA) in 1980. SGA lasted for 15 years until it became the Illinois Student Government (ISG) in 1995. ISG lasted until 2004.[159]

The current university student government, created in 2004, is the Illinois Student Senate, a combined undergraduate and graduate student senate with 54 voting members. The student senators are elected by college and represent the students in the Urbana-Champaign Senate (which comprises both faculty and students), as well as on a variety of faculty and administrative committees, and are led by an internally elected executive board of a President, External Vice President, Internal Vice President, and Treasurer. As of 2012[update], the executive board is supported by an executive staff consisting of a Chief of Staff, Clerk of the Senate, Parliamentarian, Director of Communications, Intern Coordinator, and the Historian of the Senate.[160]

Residence halls

[edit]

The university provides housing for undergraduates through 24 residence halls in both Urbana and Champaign. Incoming freshmen are required to live in student housing (campus or certified) their first year on campus. The university also maintains two graduate residence halls, which are restricted to students who are sophomores or above, and three university-owned apartment complexes. Some undergraduates choose to move into apartments or the Greek houses after their first year. There are a number of private dormitories around campus, as well as 15 private, certified residences that partner with the university to offer a variety of different housing options, including ones that are cooperatives, single-gender or religiously affiliated.[161] The university is known for being one of the first universities to provide accommodations for students with disabilities.[162] In 2015, the University of Illinois announced that they would be naming its newest residence hall after Carlos Montezuma also known as Wassaja. Wassaja is the first Native American graduate and is believed to be one of the first Native Americans to receive a medical degree.[163]

Libraries and museums

[edit]

Among universities in North America, only the collections of Harvard are larger.[164] Currently, the University of Illinois' 20+ departmental libraries and divisions hold more than 24 million items, including more than 12 million print volumes.[26] As of 2012[update], it had also the largest "browsable" university library in the United States, with 5 million volumes directly accessible in stacks in a single location.[165] University of Illinois also has the largest public engineering library (Grainger Engineering Library) in the country.[166][26][167] In addition to the main library building, which houses numerous subject-oriented libraries, the Isaac Funk Family Library on the South Quad serves the College of Agriculture, Consumer, and Environmental Sciences and the Grainger Engineering Library Information Center serves the College of Engineering on the John Bardeen Quad.

Residence Hall Library System is one of three in the nation.[168][169] The Residence Hall Libraries were created in 1948 to serve the educational, recreational, and cultural information needs of first- and second-year undergraduate students residing in the residence halls, and the living-learning communities within the residence halls. The collection also serves University Housing staff as well as the larger campus community.[170] The Rare Book & Manuscript Library (RBML) is one of the Special collections units within the University Library.[171] The RBML is one of the largest special collections repositories in the United States.[172][173][174][175]

The university has several museums, galleries, and archives which include Krannert Art Museum, Sousa Archives and Center for American Music and Spurlock Museum. Gallery and exhibit locations include Krannert Center for the Performing Arts and at the School of Art and Design.

The Illinois Open Publishing Network (IOPN) is hosted and coordinated by the University of Illinois Urbana-Champaign Library, offering publishing services to members of the University of Illinois Urbana-Champaign community, to disseminate open access scholarly publications.[176]

Recreation

[edit]

The campus has two main recreation facilities, the Activities and Recreation Center (ARC) and the Campus Recreation Center – East (CRCE). Originally known as the Intramural Physical Education Building (IMPE) and opened in 1971, IMPE was renovated in 2006 and reopened in August 2008 as the ARC.[177] The renovations expanded the facility, adding 103,433 square feet to the existing structure and costing $54.9 million. This facility is touted by the university as "one of the country's largest on-campus recreation centers." CRCE was originally known as the Satellite Recreation Center and was opened in 1989. The facility was renovated in 2005 to expand the space and update equipment, officially reopening in March 2005 as CRCE.[178]

Transportation

[edit]

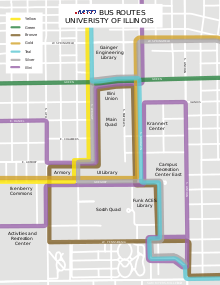

The bus system that operates throughout the campus and community is operated by the Champaign-Urbana Mass Transit District. The MTD receives a student-approved transportation fee from the university, which provides unlimited access for university students, faculty, and staff.

Daily Amtrak trains through Illinois Terminal connect Champaign-Urbana with Chicago and Carbondale, Illinois. This includes the corridor service Illini and Saluki and the long-distance City of New Orleans, which provides a direct route to Memphis, Tennessee; Jackson, Mississippi; and New Orleans, Louisiana southbound, in addition to Chicago northbound.

Willard Airport, opened in 1954 and is named for former University of Illinois president Arthur Cutts Willard. The airport is located in Savoy. Willard Airport is home to University research projects and the university's Institute of Aviation, along with flights from American Airlines.

Security

[edit]The University of Illinois has a dedicated police department, UIPD, which operates independently from CPD, the department that serves the surrounding Champaign area.

On June 9, 2017, Yingying Zhang, a Chinese international student, was abducted and murdered in a case that made national headlines at the time. The university subsequently announced plans to install additional, high-definition, security cameras across the campus.[179]

On April 18, 2022, Sayed A. Quraishi, a 23-year old man who had recently graduated from the university, assaulted a Jewish student outside of the campus' Hillel building during an anti-Israel protest organized by Students for Justice in Palestine (SJP). Quraishi was subsequently charged with a hate crime.[180]

In July 2022, the university announced that it was partnering with local businesses to invest $300,000 to combat violent crime in Champaign County.[181]

In September 2022, the City of Champaign transferred responsibility for a large swath of Campustown from CPD (Champaign Police Department) to UIPD, claiming that doing so would reduce response times and improve the quality of service. As part of the jurisdictional reforms, the city agreed to pay a substantial portion of the cost to hire seven new officers to patrol the new coverage area.[182]

Violent crime fell sharply in 2022 compared to the year prior, with shootings and homicides declining by 50 and 47 percent, respectively. The city attributed the decrease in crime to improved staffing levels and the installation of automatic license plate readers.[183]

Athletics

[edit]

U of I's Division of Intercollegiate Athletics fields teams for ten men's and eleven women's varsity sports. The university participates in the NCAA's Division I. The university's athletic teams are known as the Fighting Illini. The university operates a number of athletic facilities, including Memorial Stadium for football, the State Farm Center for men's and women's basketball, and the Atkins Tennis Center for men's and women's tennis. The men's NCAA basketball team had a dream run in the 2005 season, with Bruce Weber's Fighting Illini tying the record for most victories in a season. Their run ended 37–2 with a loss to the North Carolina Tar Heels in the national championship game. Illinois is a member of the Big Ten Conference. Notable among a number of songs commonly played and sung at various events such as commencement and convocation, and athletic games are: Illinois Loyalty, the school song; Oskee Wow Wow, the fight song; and Hail to the Orange, the alma mater.

On October 15, 1910, the Illinois football team defeated the University of Chicago Maroons with a score of 3–0 in a game that Illinois claims was the first homecoming game, though several other schools claim to have held the first homecoming as well.[185][186] On November 10, 2007, the unranked Illinois football team defeated the No. 1 ranked Ohio State football team in Ohio Stadium, the first time that the Illini beat a No. 1 ranked team on the road.

The University of Illinois Ice Arena is home to the university's club college ice hockey team competing at the ACHA Division I level and is also available for recreational use through the Division of Campus Recreation. It was built in 1931 and designed by Chicago architecture firm Holabird and Root, the same firm that designed the University of Illinois Memorial Stadium and Chicago's Soldier Field. It is located on Armory Drive across from the Armory. The structure features four rows of bleacher seating in an elevated balcony that runs the length of the ice rink on either side. These bleachers provide seating for roughly 1,200 fans, with standing room and bench seating available underneath. Because of this set-up the team benches are actually directly underneath the stands.[187]

In 2015, the university began Mandarin Chinese broadcasts of its American football games as a service to its Chinese international students.[140]

Mascot

[edit]Chief Illiniwek, also referred to as "The Chief", was from 1926 to 2007 the official symbol of the University of Illinois in university intercollegiate athletic programs. The Chief was typically portrayed by a student dressed in Sioux regalia. Several groups protested that the use of a Native American figure and indigenous customs in such a manner was inappropriate and promoted ethnic stereotypes. In August 2005, the National Collegiate Athletic Association expressed disapproval of the university's use of a "hostile or abusive" image.[188] While initially proposing a consensus approach to the decision about the Chief, the board in 2007 decided that the Chief, its name, image and regalia should be officially retired. Nevertheless, the controversy continues on campus with some students unofficially maintaining the Chief. Complaints continue that indigenous students feel insulted when images of the Chief continue to be present on campus.[189] The effort to resolve the controversy has included the work of a committee, which issued a report of its "critical conversations" that included over 600 participants representing all sides.[190]

Notable alumni and faculty

[edit]- Notable University of Illinois Urbana-Champaign alumni include:

-

Yi Gang (PhD), 12th Governor of the People's Bank of China

-

Neel Kashkari (BS, MS), President and CEO of the Federal Reserve Bank of Minneapolis

-

Hugh Hefner (BA), Founder of Playboy Enterprises, Inc.

-

Lew Allen (MS, PhD), 10th Chief of Staff of the United States Air Force

-

Giorgi Kvirikashvili (MS), 12th Prime Minister of Georgia

-

Rafael Correa (MS, PhD), 45th President of Ecuador

-

Fidel V. Ramos (MS), 12th President of the Philippines

-

Lin Chuan (PhD), 52nd Premier of the Republic of China

-

Mustafa Khalil (PhD), 40th Prime Minister of Egypt

-

Dorothy Day, journalist and social activist

-

Red Grange, football player

Twenty-seven alumni and faculty members of the University of Illinois Urbana-Champaign have won a Pulitzer Prize.[191] As of 2019[update], the University of Illinois Urbana-Champaign alumni, faculty, and researchers include 24 Nobel laureates (including 11 alumni). In particular, John Bardeen is the only person to have won two Nobel prizes in physics, having done so in 1956 and 1972 while on faculty at the university. In 2003, two faculty members won Nobel prizes in different disciplines: Paul C. Lauterbur for physiology or medicine, and Anthony Leggett for physics.

The alumni of the university have created companies and products such as Netscape Communications (formerly Mosaic) (Marc Andreessen),[192] AMD (Jerry Sanders),[192] PayPal (Max Levchin),[192] Playboy (Hugh Hefner), National Football League (George Halas), Siebel Systems and C3.ai (Thomas Siebel),[192] Mortal Kombat (Ed Boon), CDW (Michael Krasny), YouTube (Steve Chen and Jawed Karim),[192] THX (Tomlinson Holman), Andreessen Horowitz (Marc Andreessen), Oracle (Larry Ellison[192] and Bob Miner), Lotus (Ray Ozzie),[192] Yelp! (Jeremy Stoppelman[192] and Russel Simmons), Safari (Dave Hyatt), Firefox (Joe Hewitt), W. W. Grainger (William Wallace Grainger), Delta Air Lines (C. E. Woolman), Beckman Instruments (Arnold Beckman), BET (Robert L. Johnson) and Tesla Motors (Martin Eberhard).[192]

Alumni and faculty have invented the LED and the quantum well laser (Nick Holonyak, B.S. 1950, M.S. 1951, Ph.D. 1954), DSL (John Cioffi, B.S. 1978), JavaScript (Brendan Eich, M.S. 1986),[192] the integrated circuit (Jack Kilby, B.S. 1947), the transistor (John Bardeen, faculty, 1951–1991), the pH meter (Arnold Beckman, B.S. 1922, M.S. 1923), MRI (Paul C. Lauterbur), the plasma screen (Donald Bitzer, B.S. 1955, M.S. 1956, Ph.D. 1960), color plasma display (Larry F. Weber, B.S. 1968 M.S. 1971 Ph.D. 1975), the training methodology called PdEI and the coin counter (James P. Liautaud, B.S. 1963), the statistical algorithm called Gibbs sampling in computer vision and the machine learning technique called random forests (Donald Geman, B.A. 1965), and are responsible for the structural design of such buildings as the Willis Tower, the John Hancock Center, and the Burj Khalifa.[193]

Mathematician Richard Hamming, known for the Hamming code and Hamming distance, earned a PhD in mathematics from the university's Mathematics Department in 1942.[194] Primetime Emmy Award-winning engineer Alan Bovik (B.S. 1980, M.S. 1982, Ph.D. 1984) invented neuroscience-based video quality measurement tools that pervade television, social media and home cinema.[195] Structural engineer Fazlur Rahman Khan earned two master's degrees, and a PhD in structural engineering from the university.[196]

Alumni have also led several companies, including McDonald's, Goldman Sachs, BP, Kodak, Shell, General Motors, AT&T, and General Electric and others.

Alumni have founded many organizations, including the Susan G. Komen for the Cure and Project Gutenberg, and have served in a wide variety of government and public interest roles. Rafael Correa, President of The Republic of Ecuador from 2007 to 2017, secured his M.S. and PhD degrees from the university's Economics Department in 1999 and 2001 respectively.[197] Nathan C. Ricker attended U of I and in 1873 was the first person to graduate in the United States with a certificate in architecture. Mary L. Page, the first woman to obtain a degree in architecture, also graduated from U of I.[198] Disability rights activist and co-organizer of the 504 Sit-in, Kitty Cone, attended during the 1960s, but left six hours short of her degree to continue her activism in New York.[199]

In sports, baseball pitcher Ken Holtzman was a two-time All Star major leaguer, and threw two no-hitters in his career.[200] In sports entertainment, David Otunga became a two-time WWE Tag Team Champion.

Eta Kappa Nu (ΗΚΝ) was founded at the University of Illinois Urbana-Champaign as the national honor society for electrical engineering in 1904. Maurice LeRoy Carr (B.S. 1905) and Edmund B. Wheeler (B.S. 1905) were part of the founding group of ten students and they served as the first and second national presidents of ΗΚΝ. The Eta Kappa Nu organization is now the international honor society for IEEE as the IEEE-Eta Kappa Nu (IEEE-ΗΚΝ).[201] The U of I collegiate chapter is known as the Alpha Chapter of ΗΚΝ.[202] Lowell P. Hager was the head of the Department of Biochemistry from 1969 until 1989 and was elected to the National Academy of Sciences in 1995.[203]

James Holzhauer, the third-highest-earning American game show contestant of all time and holder of several Jeopardy! records, attended University of Illinois Urbana-Champaign. He was a member of the Worldwide Youth in Science and Engineering Team that won the state competition for the university, contributing by taking first place in physics and second in math.[204] Holzhauer graduated with a Bachelor of Science degree in mathematics in 2005.[205]

Notes

[edit]- ^ Other consists of Multiracial Americans and those who prefer to not say.

- ^ The percentage of students who received an income-based federal Pell grant intended for low-income students.

- ^ The percentage of students who are a part of the American middle class at the bare minimum.

- ^ Jesse Jackson was an admitted and matriculated student at UIUC. After attending classes for a semester, he transferred.

- ^ Larry Ellison was an admitted and matriculated student at UIUC.

References

[edit]- ^ "HLC - University of Illinois Urbana Champaign".

- ^ As of June 30, 2023. "U.S. and Canadian 2023 NCSE Participating Institutions Listed by Fiscal Year 2023 Endowment Market Value, Change in Market Value from FY22 to FY23, and FY23 Endowment Market Values Per Full-time Equivalent Student" (XLSX). National Association of College and University Business Officers (NACUBO). February 15, 2024. Archived from the original on May 23, 2024. Retrieved July 12, 2024.

- ^ "Budget". uillinois.edu. University of Illinois Foundation. Archived from the original on December 3, 2022. Retrieved December 5, 2022.

- ^ "Meet the Chancellor". Illinois.edu. Archived from the original on September 27, 2016. Retrieved September 26, 2016.

- ^ "Staff & Office Locations". uillinois.edu. University of Illinois System. Archived from the original on January 28, 2021. Retrieved December 14, 2020.

- ^ "Coleman, John". illinois.edu. Office of the Provost, University of Illinois. Retrieved August 10, 2023.

- ^ "2020-2021 Campus Profile - Campus Total". dmi.illinois.edu. Archived from the original on September 9, 2021. Retrieved September 9, 2021.

- ^ a b c "Illinois welcomes largest number of students in university history". illinois.edu. University of Illinois Urbana-Champaign. September 11, 2024. Retrieved October 14, 2024.

- ^ a b "Campus Facts". illinois.edu. University of Illinois Urbana-Champaign. Archived from the original on August 28, 2017. Retrieved August 30, 2017.

- ^ "College Navigator - University of Illinois Urbana-Champaign". National Center for Education Statistics. US Department of Education. Archived from the original on June 2, 2022. Retrieved February 23, 2022.

- ^ "University of Illinois Urbana-Champaign Visual Identity: Color". Retrieved November 13, 2022.

- ^ "Our name". Office of Strategic Marketing and Branding, University of Illinois Urbana-Champaign. Archived from the original on December 2, 2021. Retrieved November 24, 2021.

- ^ "Campus Administrative Manual – Urbana–Champaign Campus Designation". marketing.illinois.edu. University of Illinois Office of the Chancellor. Archived from the original on March 6, 2016. Retrieved August 14, 2016.

- ^ "Academics". illinois.edu. University of Illinois Urbana–Champaign. Archived from the original on March 25, 2018. Retrieved March 20, 2018.

- ^ "PROSPECTUS FOR THE POSITION OF CHANCELLOR, University of Illinois at Urbana-Champaign and VICE PRESIDENT, University of Illinois" (PDF). illinois.edu. University of Illinois President's Office. Spring 2016. Archived (PDF) from the original on June 30, 2018. Retrieved May 16, 2019.

- ^ a b c "By the Numbers - Office of the Vice Chancellor for Research". research.illinois.edu. Archived from the original on July 31, 2016. Retrieved August 6, 2016.

- ^ "Carnegie Classifications Institution Lookup". carnegieclassifications.iu.edu. Center for Postsecondary Education. Archived from the original on July 26, 2020. Retrieved July 25, 2020.

- ^ a b "Table 20. Higher education R&D expenditures, ranked by FY 2018 R&D expenditures: FYs 2009–18". ncsesdata.nsf.gov. National Science Foundation. Archived from the original on September 30, 2020. Retrieved July 25, 2020.

- ^ Mian, Anam; Roebuck, Gary (2020). ARL Statistics 2020. Washington, DC: Association of Research Libraries. Archived from the original on February 3, 2023. Retrieved March 12, 2023.

- ^ "The National Center for Supercomputing Applications at the University of Illinois at Urbana-Champaign". ncsa.illinois.edu. Archived from the original on December 24, 2012. Retrieved December 11, 2012.

- ^ "Daily Illini". Illinois Digital Newspaper Collections. January 1, 1879. Archived from the original on July 21, 2015. Retrieved July 20, 2015.

- ^ Illini Years: A Picture History of the University of Illinois (1950). p. 6

- ^ a b c Brichford, Maynard. "A Brief History of the University of Illinois". A Brief History of the University of Illinois. University of Illinois Archives. Archived from the original on August 23, 2015. Retrieved September 17, 2015.

- ^ a b Brichford, Maynard. (1983), A Brief History of the University of Illinois Archived June 15, 2007, at the Wayback Machine

- ^ McGinty, Alice. "The Story of Champaign-Urbana" Archived February 14, 2016, at the Wayback Machine Champaign Public Library

- ^ a b c "Facts | Illinois". Illinois.edu. Archived from the original on August 11, 2011. Retrieved July 29, 2012.

- ^ "About the University Library". About the University Library. University of Illinois. Archived from the original on October 3, 2015. Retrieved September 17, 2015.

- ^ "University of Illinois Campus Tour- Alma Mater". Archived from the original on July 8, 2010. Retrieved June 13, 2007.

- ^ a b c Leetaru, Kalev. "Hallene Gateway". University of Illinois: Virtual Campus Tour. UIHistories. Archived from the original on October 18, 2015. Retrieved September 18, 2015.

- ^ Crow, Michael M.; Dabars, William B. (2015). Designing the New American University. Baltimore: Johns Hopkins University Press. pp. 17–18. ISBN 9781421417233. Retrieved May 28, 2017. The quoted sentence is Crow and Dabars' paraphrasing of Geiger's analysis.

- ^ Geiger, Roger L. (1986). To Advance Knowledge: The Growth of American Research Universities, 1900–1940 (2004 ed.). New Brunswick, New Jersey: Transaction Publishers. p. 3. ISBN 9781412840088. Archived from the original on March 14, 2023. Retrieved May 28, 2021.

- ^ Solberg, Winton U. (2004) "Edmund Janes James Builds a Library: The University of Illinois Library, 1904–1920" Libraries & Culture 39(1): pp. 36–75 [67]

- ^ Mary Timmins, "Enter the Dragon" Archived September 6, 2015, at the Wayback Machine, Illinois Alumni Magazine December 15, 2011.

- ^ "Alma Mater". University of Illinois: Virtual Campus Tour. University of illinois. Archived from the original on October 18, 2015. Retrieved September 18, 2015.

- ^ "David . Henry, 89, President Of Illinois U. in Time of Tumult". The New York Times. September 7, 1995. Archived from the original on May 19, 2017. Retrieved February 20, 2017.

- ^ Peterson, Doug, 2015, "The (Water) Fighting Illini," Illinois Alumni Spring 2015, pp. 34–35. https://uiaa.org/2015/04/09/memory-lane-the-water-fighting-illini/

- ^ "University of Illinois FY2010 Budget Request" (PDF). Archived (PDF) from the original on June 16, 2011. Retrieved May 26, 2011.

- ^ a b "Budget by Source of Funds | Stewarding Excellence @ Illinois". Oc.illinois.edu. Archived from the original on March 5, 2012. Retrieved July 29, 2012.

- ^ "Frequently Asked Questions". Carle Illinois College of Medicine. Archived from the original on June 1, 2015. Retrieved April 27, 2015.

- ^ a b "U. of I. pitches new medical school". Chicago Tribune. September 30, 2015. Archived from the original on April 20, 2015. Retrieved April 27, 2015.

- ^ a b "U. of I., Carle moving forward with the first engineering-based college of medicine". Illinois News Bureau. March 12, 2015. Archived from the original on May 2, 2015. Retrieved April 27, 2015.

- ^ "Core curriculum committee formed for Carle Illinois College of Medicine" (PDF). University of Illinois. December 10, 2015. Archived from the original (PDF) on March 28, 2016. Retrieved June 23, 2016.

- ^ "University of Illinois Urbana-Champaign announces the Siebel School of Computing and Data Science". April 24, 2024. Retrieved August 2, 2024.

- ^ Lee, William (October 26, 2017). "Couple donate $150 million to University of Illinois in its largest gift ever". chicagotribune.com. Archived from the original on May 3, 2023. Retrieved July 9, 2021.

- ^

- "2020 CENSUS - CENSUS BLOCK MAP: Champaign city, IL" (PDF). U.S. Census Bureau. pp. 2, 4 (PDF p. 3, 5/5). Retrieved July 1, 2023.

Univ of Illinois

- "2020 CENSUS - CENSUS BLOCK MAP: Urbana city, IL" (PDF). U.S. Census Bureau. p. 2 (PDF p. 3/4). Retrieved July 1, 2023.

Univ of Illinois

- Compare to: - "Campus Map" (PDF). University of Illinois. Retrieved July 1, 2023.

- "2020 CENSUS - CENSUS BLOCK MAP: Champaign city, IL" (PDF). U.S. Census Bureau. pp. 2, 4 (PDF p. 3, 5/5). Retrieved July 1, 2023.

- ^ "Campus map". Archived from the original on November 7, 2005. Retrieved November 23, 2005.

- ^ "Campus Landmarks". Archived from the original on August 19, 2007. Retrieved August 30, 2007.

- ^ Shari L. Ellertson. "Expenditures on O&M at America's Most Beautiful Campuses". APPA. Archived from the original on February 19, 2008. Retrieved July 24, 2007.

- ^ Committee on Campus Operations. UIUC Senate Archived September 6, 2006, at the Wayback Machine. April 26, 2004.

- ^ "University of Illinois, Urbana-Champaign | Scorecard | Institutions | STARS Reports". Archived from the original on February 7, 2023. Retrieved March 23, 2023.

- ^ "College Scorecard: University of Illinois Urbana-Champaign". United States Department of Education. Retrieved September 7, 2024.

- ^ a b "UIUC Common Data Set 2023-2024". University of Illinois Urbana-Champaign. Retrieved September 17, 2024.

- ^ "UIUC Acceptance Data". University of Illinois Urbana-Champaign. Retrieved December 13, 2023.

- ^ a b c "Admit Rates". University of Illinois Urbana-Champaign. Retrieved November 1, 2024.

- ^ "2021 Best Undergraduate Computer Science Programs Rankings". Archived from the original on October 29, 2020.

- ^ "Computer Science Open Rankings". Archived from the original on February 4, 2021. Retrieved January 30, 2021.

- ^ "Jeff Erickson answer to Is the UIUC selective for CS?".

- ^ a b "first-year admit rates for 2022 - official". admissions.illinois.edu. Archived from the original on September 9, 2022. Retrieved August 23, 2022.

- ^ Communications, Grainger Engineering Office of Marketing and. "Rankings & Statistics". cs.illinois.edu. Archived from the original on October 20, 2020. Retrieved October 25, 2020.

- ^ "UIUC Common Data Set 2020-2021". University of Illinois Urbana-Champaign. Archived from the original on November 12, 2022. Retrieved November 12, 2022.

- ^ "UIUC Common Data Set 2019-2020". University of Illinois Urbana-Champaign. Archived from the original on November 12, 2022. Retrieved November 12, 2022.

- ^ "UIUC Common Data Set 2018-2019". University of Illinois Urbana-Champaign. Archived from the original on November 16, 2022. Retrieved November 12, 2022.

- ^ "UIUC Common Data Set 2017-2018". University of Illinois Urbana-Champaign. Archived from the original on November 16, 2022. Retrieved November 12, 2022.

- ^ "UIUC Common Data Set 2016-2017". University of Illinois Urbana-Champaign. Archived from the original on November 12, 2022. Retrieved November 12, 2022.

- ^ "First-Year Enrollment 10th Day Report 2022" (PDF). University of Illinois at Urbana-Champaign. Archived (PDF) from the original on December 4, 2022. Retrieved February 14, 2023.

- ^ "First-Year Class Profile". University of Illinois Urbana-Champaign. Retrieved November 1, 2024.

- ^ "UIUC CS Rankings & Statistics". University of Illinois Urbana-Champaign. Retrieved November 1, 2024.

- ^ "Illinois' very own college admissions scandal: Editorials from a shameful chapter in U. of I. history". Chicago Tribune. March 13, 2019. Archived from the original on October 6, 2020.

- ^ "University of Illinois Academics". University of Illinois Urbana-Champaign. Archived from the original on February 10, 2017. Retrieved February 15, 2017.

- ^ Jackson, Cheryl V. "The online MBA: Advantages, disadvantages in growing trend". Chicago Tribune. Archived from the original on January 22, 2018. Retrieved January 21, 2018.

- ^ Wang, Amy X. "Coursera is offering a way to get a real master's degree for a lot less money". Quartz. Archived from the original on January 22, 2018. Retrieved January 21, 2018.

- ^ "Best Graduate Computer Science Programs". U.S. News & World Report. January 21, 2018. Archived from the original on March 14, 2017. Retrieved January 21, 2018.

- ^ "University of Illinois at Urbana–Champaign, HEC Paris Launch Master's Degrees on Coursera – Campus Technology". Campus Technology. Archived from the original on January 22, 2018. Retrieved January 21, 2018.

- ^ "Master's in Accounting – iMSA by University of Illinois | Coursera". Coursera. Archived from the original on January 22, 2018. Retrieved January 21, 2018.

- ^ "Master of Computer Science in Data Science | Coursera". Coursera. Archived from the original on January 22, 2018. Retrieved January 21, 2018.

- ^ "America's Top Colleges 2024". Forbes. September 6, 2024. Retrieved September 10, 2024.

- ^ "2024-2025 Best National Universities Rankings". U.S. News & World Report. September 23, 2024. Retrieved November 22, 2024.

- ^ "2024 National University Rankings". Washington Monthly. August 25, 2024. Retrieved August 29, 2024.

- ^ "2025 Best Colleges in the U.S." The Wall Street Journal/College Pulse. September 4, 2024. Retrieved September 6, 2024.

- ^ "2024 Academic Ranking of World Universities". ShanghaiRanking Consultancy. August 15, 2024. Retrieved August 21, 2024.

- ^ "QS World University Rankings 2025". Quacquarelli Symonds. June 4, 2024. Retrieved August 9, 2024.

- ^ "World University Rankings 2024". Times Higher Education. September 27, 2023. Retrieved August 9, 2024.

- ^ "2024-2025 Best Global Universities Rankings". U.S. News & World Report. June 24, 2024. Retrieved August 9, 2024.

- ^ "THE World University Rankings 2024 by subject: computer science". October 18, 2023. Retrieved December 10, 2023.

- ^ "QS World University Rankings by Subject 2023: Computer Science and Information Systems". Retrieved December 10, 2023.

- ^ "CSRankings: Computer Science Rankings". Retrieved December 10, 2023.

- ^ "University of Illinois-Urbana-Champaign - U.S. News Best Grad School Rankings". U.S. News & World Report. Retrieved June 7, 2024.

- ^ "University of Illinois-Urbana-Champaign - U.S. News Best Global University Rankings". U.S. News & World Report. Archived from the original on February 28, 2020. Retrieved October 22, 2020.

- ^ "University of Illinois--Urbana-Champaign Rankings". U.S. News & World Report. Archived from the original on October 7, 2019. Retrieved October 22, 2020.

- ^ "2020 National University Rankings". Washington Monthly. Archived from the original on September 1, 2020. Retrieved September 1, 2020.

- ^ "Kiplinger's Best College Values – Public Colleges". The Kiplinger Washington Editors. July 2019. Archived from the original on August 23, 2019. Retrieved September 11, 2019.

- ^ "The Top Schools For Urban Planners". Planetizen - Urban Planning News, Jobs, and Education. Archived from the original on July 3, 2019. Retrieved September 11, 2019.

- ^ Greene, Howard R.; Greene, Matthew W. (2001). The public ivies: America's flagship public universities (1st ed.). New York: Cliff Street Books. ISBN 978-0060934590.

- ^ "Top party schools named by the Princeton Review". CBS News. August 3, 2015. Archived from the original on November 17, 2015. Retrieved November 13, 2015.

- ^ "Academic Ranking of World Universities 2016". ShanghaiRanking Consultancy. Archived from the original on July 31, 2019. Retrieved September 11, 2019.

- ^ "CWUR - World University Rankings 2019-2020". cwur.org. Archived from the original on September 7, 2019. Retrieved September 11, 2019.

- ^ "The top 50 universities by reputation 2018". Times Higher Education (THE). May 30, 2018. Archived from the original on June 12, 2018. Retrieved June 7, 2018.

- ^ "Research- The Center for Measuring University Performance" (PDF). Mup.asu.edu. Archived from the original (PDF) on October 20, 2012. Retrieved July 29, 2012.

- ^ "Research- The Center for Measuring University Performance". Mup.asu.edu. Archived from the original on June 17, 2012. Retrieved July 29, 2012.

- ^ "About Us: Buildings and Facilities – ECE ILLINOIS | University of Illinois at Urbana–Champaign". Ece.uiuc.edu. Archived from the original on August 28, 2008. Retrieved July 29, 2012.

- ^ "National Science Board Approves Funds for Petascale Computing Systems". Archived from the original on August 31, 2007. Retrieved August 24, 2007.

- ^ Feldman, Michael (November 14, 2011). "NCSA Signs Up Cray for Blue Waters Redo". HPC Wire. Archived from the original on February 16, 2013. Retrieved December 11, 2012.

- ^ "Blue Waters system stats". Ncsa.illinois.edu. Archived from the original on October 28, 2012. Retrieved December 11, 2012.

- ^ "Blue Waters One Year Later: Delivering Sustained Petascale Science". Nncsa.illinois.edu. Archived from the original on January 25, 2013. Retrieved December 11, 2012.

- ^ "Cahokiamounds.com". Cahokiamounds.com. Archived from the original on October 6, 2008.

- ^ "EnterpriseWorks Incubator". Research Park at Illinois. Archived from the original on May 7, 2015. Retrieved April 27, 2015.

- ^ "Urbana Named a Top Startup City by Popular Mechanics". Research Park at Illinois. January 14, 2015. Archived from the original on April 30, 2015. Retrieved April 27, 2015.

- ^ "About". Research Park at Illinois. Archived from the original on May 4, 2015. Retrieved April 27, 2015.

- ^ "What is TEC?". Archived from the original on October 24, 2019. Retrieved October 24, 2019.

- ^ "Cozad New Venture Challenge". Archived from the original on October 24, 2019. Retrieved October 24, 2019.

- ^ "Silicon Valley Entrepreneurship Workshop Application Due Sept. 30, 2019". Archived from the original on October 30, 2020. Retrieved October 24, 2019.

- ^ "NSF Innovation Corps". Archived from the original on November 4, 2019. Retrieved October 24, 2019.

- ^ "Illinois I-Corps". Archived from the original on July 9, 2019. Retrieved October 24, 2019.

- ^ "SocialFuse". Archived from the original on October 24, 2019. Retrieved November 14, 2019.

- ^ Max-Planck-Institut für Plasmaphysik (September 22, 2014). "WEGA fusion experiment passed on to the USA". Phys.org. Archived from the original on November 25, 2021. Retrieved December 3, 2021.

- ^ Semaca, Michael (September 15, 2016). "University's nuclear fusion device receives million dollar grant". The Daily Illini. Archived from the original on November 9, 2021. Retrieved December 3, 2021.

- ^ "AVS zeichnet Mark C. Hersam und David N. Ruzik" [American Vacuum Society honors Mark C. Hersam and David N. Ruzik]. Physik Journal (in German). October 16, 2020. Archived from the original on November 9, 2021. Retrieved December 3, 2021.

- ^ "Remarks by Bill Gates". Microsoft. Archived from the original on July 5, 2007. Retrieved July 5, 2007.

- ^ Department of Computer Science. "News & Events | Department of Computer Science at Illinois". Cs.uiuc.edu. Archived from the original on October 16, 2007. Retrieved July 29, 2012.

- ^ "Computer Science Department Calendar". Archived from the original on October 16, 2007. Retrieved June 21, 2016.

- ^ Bollinger, Karen (March 7, 2016). "Illinois Earns Highest Honors from UPCEA". Illinois-Online. Archived from the original on April 7, 2016. Retrieved March 30, 2016.

- ^ "John Bardeen, Nobelist, Inventor of Transistor, Dies". Washington Post. January 31, 1991. Archived from the original on November 2, 2012. Retrieved August 3, 2007.

- ^ Levey Larson, Debra (August 2003). "Supersweet sweet corn: 50 years in the making". Inside Illinois. 23 (3). University of Illinois Urbana-Champaign. Archived from the original on October 12, 2008. Retrieved September 3, 2009.

- ^ Andrew Stiller, "Hiller, Lejaren (Arthur)", Grove Music Online (reviewed December 3, 2010; accessed December 14, 2014).

- ^ Denis L. Baggi, "The Role of Computer Technology in Music and Musicology Archived July 22, 2011, at the Wayback Machine", lim.dico.unimi.it (December 9, 1998).

- ^ "The LLVM Compiler Infrastructure Project". llvm.org. Archived from the original on May 3, 2004. Retrieved January 20, 2017.

- ^ Vetter, Ronald J. (October 1994). "Mosaic and the World-Wide Web" (PDF). North Dakota State University. Archived from the original (PDF) on August 24, 2014. Retrieved November 20, 2010.

- ^ Don Bitzer, Email

- ^ CSL Quarterly Report for June, July, August 1960 (Report). Coordinated Science Laboratory, University of Illinois. September 1960.

- ^ "100 Important Innovations That Came From University Research - Online Universities". OnlineUniversities.com. August 27, 2012. Archived from the original on May 16, 2019. Retrieved May 16, 2019.

- ^ "Welcome to the new Talkomatic : Homepage". Talko.cc. Archived from the original on December 4, 2021. Retrieved February 23, 2022.

- ^ Falk, Joni K.; Drayton, Brian (2015). Creating and Sustaining Online Professional Learning Communities. Teachers College Press. pp. 8–. ISBN 978-0807772140. Archived from the original on July 9, 2014. Retrieved May 30, 2014.

- ^ Bidgoli, Hossein (2004). The Internet Encyclopedia. John Wiley & Sons. pp. 665–. ISBN 978-0471222040. Retrieved May 30, 2014.

- ^ Tykociner, Joseph T., "Photographic recording and photoelectric reproduction of sound," Trans. SMPE, no. 16, 90-119, 1923. cited in [1] Archived December 13, 2016, at the Wayback Machine Kellogg, Edward W., History of Sound Motion Pictures, First Installment. Journal of the SMPTE, 1955, June, pp. 291–302. retrieved December 17, 2006

- ^ "Illinois VENTURES – UofI Alumni Founded Companies". illinoisventures.com. Archived from the original on December 1, 2017. Retrieved November 23, 2017.

- ^ Afridi, Ali (July 23, 2015). "Tech companies started by University of Illinois alum". Medium. Archived from the original on December 28, 2017. Retrieved December 27, 2017.

- ^ "Jerry Colangelo profile". Nba.com. Archived from the original on July 13, 2018. Retrieved December 27, 2017.

- ^ "College Scorecard: University of Illinois Urbana-Champaign". United States Department of Education. Retrieved September 7, 2024.

- ^ "Enrollment Spring 2018". UIUC Student Enrollment Spring 2018. UIUC. Archived from the original on February 20, 2018. Retrieved February 2, 2018.

- ^ a b "Illinois launches Chinese-language broadcasts of football games Archived July 10, 2017, at the Wayback Machine." The Guardian. Saturday September 19, 2015. Retrieved on October 16, 2015.

- ^ "Enrollment 2015". UIUC Student Enrollment. UIUC campus. Archived from the original on September 15, 2015. Retrieved September 18, 2015.

- ^ a b c "Students". Campus Facts. University of Illinois Urbana Champaign. Archived from the original on September 5, 2015. Retrieved September 18, 2015.

- ^ a b "Enrollment Fall 2015". UIUC Student Enrollment Fall 2015. UIUC. Archived from the original on October 18, 2015. Retrieved October 16, 2015.

- ^ Elizabeth Redden, "The University of China at Illinois," Inside Higher Education Jan 7, 2015 Archived January 7, 2015, at the Wayback Machine

- ^ "University of Illinois at Urbana–Champaign". Illinois.collegiatelink.net. Archived from the original on July 24, 2012. Retrieved July 29, 2012.

- ^ "Programs and Activities". Union.uiuc.edu. Archived from the original on June 22, 2012. Retrieved July 29, 2012.

- ^ "About Us – Varsity Men's Glee Club". Archived from the original on October 11, 2016. Retrieved June 21, 2016.