Newseum

| |

Newseum in 2008 | |

Location of Newseum in Washington, D.C. | |

| Established | April 18, 1997 |

|---|---|

| Dissolved | December 31, 2019[1][2] |

| Location | 555 Pennsylvania Avenue NW Washington, D.C., United States |

| Coordinates | 38°53′36″N 77°01′09″W / 38.893219°N 77.01924°W |

The Newseum was an American museum at 555 Pennsylvania Avenue NW, in Washington, D.C., dedicated to news and journalism that promoted free expression and the First Amendment to the United States Constitution, while tracing the evolution of communication.

The purpose of the museum, funded by the Freedom Forum, a nonpartisan U.S. foundation dedicated to freedom of the press, freedom of speech, and freedom of thought, was to help the public and the media understand each other.[3]

The seven-level, 250,000-square-foot (23,000 m2) museum was located in Washington, D.C., and featured fifteen theaters and fifteen galleries. Its Berlin Wall Gallery included the largest display of sections of the wall outside Germany. The Today's Front Pages Gallery presented daily front pages from more than 80 international newspapers. The Today's Front Pages Gallery is still available on the Newseum's website, along with a few other galleries. Other galleries presented topics including the First Amendment, world press freedom, news history, the September 11 attacks, and the history of the Internet, TV, and radio.

It opened at its first location in Rosslyn, Virginia, on April 18, 1997, and on April 11, 2008, it opened at its last location. As of December 31, 2019, the Newseum had closed its doors[4] and many exhibits and artifacts were put into storage or returned to their owners.

History

[edit]

Freedom Forum is a non-profit organization founded in 1991 by publisher Al Neuharth, founder of the newspaper USA Today, based on the previous Gannett Foundation.[5] Freedom Forum opened the Newseum in Arlington, Virginia, in 1997. Prior to opening in Virginia, it maintained exhibition galleries in Nashville and Manhattan, the latter in the lobby of the former IBM Building at 590 Madison Avenue. In 2000, Freedom Forum decided to move the museum across the Potomac River to downtown Washington, D.C. The original site was closed on March 3, 2002, to allow its staff to concentrate on building the new, larger museum. The new museum, built at a cost of $450 million, opened its doors to the public on April 11, 2008.[6][7]

After obtaining a location at Pennsylvania Avenue and Sixth Street NW, the former site of National Hotel, the Newseum board selected exhibit designer Ralph Appelbaum, who had designed the original site in Arlington, Virginia, and architect James Stewart Polshek, who designed the Rose Center for Earth and Space with Todd Schliemann at the American Museum of Natural History in New York City, to work on the new project.[5]

Highlights of the building design unveiled October 2002 included a façade featuring a "window on the world", 57 ft × 78 ft (17 m × 24 m), which looked out on Pennsylvania Avenue and the National Mall while letting the public see inside to the visitors and displays. It featured the 45 words of the First Amendment to the U.S. Constitution, etched into a four story tall stone panel facing Pennsylvania Avenue.

One feature carried over from the prior Arlington site was the Journalists Memorial, a glass sculpture listing the names of 2,291 journalists from around the world killed in the line of duty.[8] It was updated and rededicated annually.

The museum website was updated daily with images and PDF versions of newspaper front pages from around the world. Hard copies of selected front pages, including one from every U.S. state and Washington, D.C., were displayed in galleries within the museum and outside the front entrance.[9]

Jerry Frieheim, a 1956 graduate of the University of Missouri School of Journalism, was the first executive director of the Newseum and claims to have coined the name.[10]

Building

[edit]The 643,000-square-foot (60,000 m2) Newseum included a 90-foot (27 m) high atrium, seven levels of displays, 15 theaters, a dozen major galleries, many more smaller exhibits, two broadcast studios, and an expanded interactive newsroom. The structural engineer for this project was Leslie E. Robertson Associates.

The building featured an oval, 500-seat theater; approximately 145,500 square feet (13,520 m2) gross of housing facing Sixth and C streets; 75,000 square feet (7,000 m2) of office space for the staff of the Newseum and Freedom Forum; and more than 11,000 square feet (1,000 m2) of conference center space on two levels located directly above the museum's main atrium. The building was also known for the largest and tallest hydraulic passenger elevators in the world, with a capacity of 18,000 pounds (8,200 kg) capable of carrying up to 72 passengers when fully loaded, and a travel distance of 100 feet (30 m) that covers 7 floors. A curving glass memorial to slain journalists was located above the ground floor.[11]

Showcase environments throughout the museum were climate controlled by four microclimate control devices. These units provided a flow of humidified air to the cases through a system of distribution pipes.

ABC's This Week began broadcasting from a new studio in the Newseum on April 20, 2008, with George Stephanopoulos as host.[12] ABC moved This Week back to its Washington, D.C. bureau in June 2013 citing the network's infrequent use of the Newseum studio compared to the cost of operating and maintaining a studio there. The studio was later home to Al Jazeera America's Washington, D.C. bureau which also had editing facilities and office space in the building.[13]

Sharing the building with the Newseum were The Source, a Wolfgang Puck Restaurant, and the Newseum Residences, a collection of 135 luxury apartment homes.[14]

Critical response

[edit]Journalist Alan Rusbridger of The Guardian wrote that visitors would have "a great family day out"; he considered some of the exhibits, such as a red dress worn by Helen Thomas, "faintly ridiculous" while praising others, such as a large chunk of the actual Berlin Wall. Although writing that the Newseum displayed "self-glorification, pomposity and vanity" in an "overwhelmingly American-centric" way, he described the building design as "uplifting" and generally commended the features.[15] Michael Landauer of the Dallas Morning News praised its interactive exhibits, writing: "While the free Smithsonian museums do a fine job of housing our important artifacts, I believe the Newseum on Pennsylvania Avenue does an unparalleled job of telling our nation's story."[16] Bonnie Wach, writing for the San Francisco Chronicle praised the Newseum's interactive exhibits, calling it "a marvel of technological innovation" and citing its "seven floors of touch-screens, theaters, film and video, state-of-the-art studios, computer games, interactive kiosks, documentary footage and hands-on multimedia exhibits."[17]

Other reviewers were more critical. Nicolai Ouroussoff, architecture critic for the New York Times, panned the second Newseum building as "the latest reason to lament the state of contemporary architecture in" Washington, D.C.[18] Writing on the Newseum's content, Times culture critic Edward Rothstein wrote that "a good portion of the museum's earnestly sought attention is well deserved" but "the museum's preening does call for some skepticism."[19] Gannett's USA Today noted that while reviews of the building's architecture had been mixed, the high number of visitors was a sign that the Newseum was successful, even in a capital city full of museums.[20] James Bowman of National Review Online criticized the Newseum's interaction-heavy exhibits as overly stylistic and superficial, writing that it focuses on headline-based reporting of major world events rather than details of the events themselves.[21] The AIA Guide to the Architecture of Washington DC describes the view from the Avenue as a "barrage, with numerous elements vying for your attention. ... a virtual national television set (or computer screen)."[22]

An exhibit at the Newseum discussed the "effort to avoid bias" by journalists. It included a 2006 Gallup poll in which 44% of Americans called the media "too liberal" while only 19% found it "too conservative" as well as other comments on possible political media bias, many of which came from Fox News contributors. Jonathan Schwarz of Mother Jones criticized the exhibit and called it an example of corporate propaganda from Rupert Murdoch's News Corporation. He also argued that most of the U.S. news media is controlled by businesses who shut out stories that would counter their interests.[23] Kevin D. Williamson of National Review Online defended the Newseum, calling the criticism "nonsense concentrate" and arguing that media-owning companies have an interest in promoting non-conservative causes.[24]

Jack Shafer, co-editor of Slate, criticized the Newseum's exhibit about the career of the late NBC reporter Tim Russert. He argued that Russert's "mundane" work-space was not worthy of preservation in a museum and that Russert's accomplishments "begin at being a pretty good interviewer and end at having a lot of celebrity friends." He concluded that the Newseum is "a place where journalist celebrities begin to be worshipped as miracle-producing saints."[25]

Despite mixed reviews, the museum drew 1.7 million visitors in its first four years in DC.[5]

Al Aqsa TV controversy

[edit]In the May 2013 rededication ceremony of the Journalist Memorial, the Newseum first decided to honor two Al Aqsa TV members as part of the memorial, and then withdrew them after criticism from pro-Israeli organizations.[26] After a year-long review of the circumstances surrounding their deaths, the Newseum, in partnership with other journalism organizations decided their names would remain on the Journalists Memorial wall.[27]

Ilene Prusher, columnist for the Israeli newspaper Haaretz, said that the Newseum stepped into the "minefield" of the Arab–Israeli conflict. Al-Aqsa TV is affiliated with Hamas in the Gaza Strip, and the two deceased journalists were killed by Israeli fire in a car marked "TV". Israeli Defense Forces spokeswoman, Lt. Col. Avital Leibovich, said that they were killed deliberately, not accidentally, because they "have relevance to terror activity."[28]

Nearly all journalistic organizations hold that the men were killed in the line of duty, including the Committee to Protect Journalists, Reporters Without Borders, the International Federation of Journalists and the World Association of Newspapers and News Publishers. Human Rights Watch said that their investigation in Gaza showed no evidence that the men were involved in militant activity. NBC News chief foreign correspondent Richard Engel said at the Newseum's dedication ceremony that it was difficult to draw the line, and several reporters on the list were Syrians who were also activists who were trying to topple Bashar al-Assad's government.[29] David Carr of the New York Times said that "the evidence so far suggests that they were journalists, however partisan."[30]

Permanent exhibits

[edit]

- The New York Times—Ochs-Sulzberger Family Great Hall: Located in the atrium, a 90-foot-high screen showed the latest headlines from around the globe. A satellite replica and a Bell helicopter (formerly used by KXAS-TV in Dallas) were also suspended in the atrium.[31]

- News Corporation News History Gallery, A timeline showcased the extensive collection of newspapers and magazines. Touch-screen computers housed hundreds of digitized publications, allowing for close-up viewing, as well as interactive games, and access to a database of journalists. Included in this gallery was a 1603 English broadsheet showing the coronation of James I; a 1787 copy of the Maryland Gazette containing the new United States Constitution; The Charleston Mercury's 1860 extra enthusiastically proclaiming, "The Union Is Dissolved!"; a copy of the 1948 Chicago Daily Tribune mistakenly announcing, "Dewey Defeats Truman."[32]

- 9/11 Gallery Sponsored by Comcast, This gallery explored the coverage of September 11, 2001. A tribute to photojournalist William Biggart, who died covering the attacks, was included. Visitors got to hear his story and see some of the final photographs he took. A giant wall was covered with worldwide front pages published the following morning, and a portion of the communications antenna from the roof of the World Trade Center was on display with a timeline of the reports and bulletins that were issued as the day unfolded. A film gave additional first-person accounts from reporters and photographers who covered the story.[33]

- Pulitzer Prize Photographs Gallery, a display the most comprehensive collection of Pulitzer Prize-winning photographs ever gathered. It included every Pulitzer Prize winning entry since 1942. Some photographs included are: Raising the Flag on Iwo Jima, Burst of Joy (the joyful reunion of a returning prisoner of war and his family), a firefighter cradling a mortally injured infant after the Oklahoma City bombing.[34]

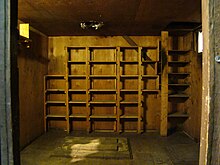

- Berlin Wall Gallery, largest display of the original wall outside of Germany. There were eight 12-foot (3.7 m) high concrete sections of wall, each weighing about three tons, and a three-story East German guard tower from Checkpoint Charlie (or "Checkpoint C"), the name given by Western Allies to Berlin's best-known East–West crossing.[35]

Cox Enterprises First Amendment Gallery: This gallery explored the role that the First Amendment's guarantee of rights (religion, speech, press, assembly and petition) has played in the United States over the past 200 years. The exhibit presented historical news clips that exemplify the five freedoms. "Our liberty depends on the freedom of the press," said Thomas Jefferson, "and that cannot be limited without being lost."[36]

Journalists Memorial: Memorialized journalists who died in the course of their duties.[37] This exhibit displayed artifacts from hazardous journalistic missions. Included was the laptop computer used by Daniel Pearl, the bloodstained notebook of Michael Weisskopf, and the 1976 Datsun 710 belonging to Don Bolles that was bombed in Phoenix. Also featured was a sobering display of more than 1,800 names written in a glass tablet, marking the deaths of those who died in pursuit of the news.[38] The gallery also contained photographs of hundreds of those journalists and access to more detailed information on every honored journalist.[37]

Operations and closures

[edit]The Newseum attracted more than 815,000 visitors a year, and its television studios hosted news broadcasts. There was an admission fee for adults.[39] The institution saw years of significant financial losses. In February 2018, these losses led to an exploration of selling its building or moving to another location.[40] In January 2019, the Freedom Forum announced The Johns Hopkins University would purchase the building for $372.5 million in order to use the space for several graduate programs.[41]

Financial losses and building closure

[edit]Despite a substantial revenue stream of rents, museum admissions, and event fees, the Newseum lost a significant amount of money.[42][43][44] In 2011, ticket sales offset just 10 percent of expenses.[45] In 2015, the museum lost more than $2.5 million on revenue of $59 million.[46]

The Freedom Forum reported that the losses had led to controversial proposals for strategies that might improve the museum's finances.[47] The issues, in part, reached back to the Washington location's construction, which had significant cost overruns. Furthermore, the numerous free museums in the National Mall area, such as those of the Smithsonian Institution and National Gallery of Art, made it difficult for visitors to justify paying the Newseum's steep entry fees.[citation needed] In August 2017, the Newseum's president, Jeffrey Herbst, resigned in the face of the museum's financial problems.[48]

In February 2018, The Washington Post reported that the Newseum was exploring the sale of its building or a move.[40][49] The Freedom Forum informed The Washington Post that it had been financing over $20 million a year in continued operating expenses. In January 2019, the Freedom Forum announced that it would sell the Newseum building to The Johns Hopkins University for $372.5 million.[41] The Washington Post subsequently published a detailed account of the financial difficulties that the museum had encountered, which included a loss of over $100 million at the time of sale due to the facility's cost having risen to $477 million. The museum closed to the public on December 31, 2019.[50]

On July 12, 2019, Johns Hopkins presented designs that showed the removal of the First Amendment etched stone panel from the building's façade.[51] In March 2021, the Freedom Forum announced that they would donate the 50-short-ton (45 t), 74 ft-tall (23 m) panel, which was in the process of being dismantled, to the National Constitution Center on Independence Mall in Philadelphia, where it is planned to be reinstalled on a 100 ft-wide (30 m) wall in the center's second-floor atrium.[52][53]

As of 2023, the building will be home to Johns Hopkins' Carey Business School.[54]

The closure of the Journalists Memorial was a blow to advocates of freedom of the press who felt there ought to be some place to commemorate journalists who had sacrificed their lives for their work. As a result, in December 2020, a bipartisan group of members of Congress brought about the enactment of a bill which authorized the construction of a memorial to fallen journalists on public land with private funds.[55] In May 2023, the Fallen Journalists Memorial Foundation started design work on the memorial.[56]

See also

[edit]References

[edit]- ^ Daley, Jason (October 3, 2019). "D.C.'s Newseum Is Closing Its Doors at the End of the Year". Smithsonian.

- ^ "Newseum is Closing; First Amendment Mission Goes Forward". Newseum. October 1, 2019. Archived from the original on December 31, 2019.

- ^ "About | Newseum". www.newseum.org. Retrieved October 6, 2016.

- ^ Hyman, Jacqueline (January 1, 2020). "The Newseum closed on Dec. 31. Here's some Jewish history you may have missed". Washington Jewish Week. Retrieved January 15, 2023.

- ^ a b c Capps, Kriston (March 7, 2019). "Is There a Future for D.C.'s Troubled Newseum?". Bloomberg.com. Retrieved October 31, 2023.

- ^ Gaynair, Gillian (February 7, 2008). "Newseum Sets Opening Date". Washington Business Journal.

- ^ Zongker, Brett (April 10, 2008). "Newseum to Open in New Home Friday". Associated Press. Archived from the original on April 14, 2008. Retrieved April 11, 2008.

- ^ Ruane, Michael E. (January 1, 2020). "As the Newseum closes its doors, pieces of history and human remains to find a new resting place". Washington Post. ISSN 0190-8286. Retrieved August 27, 2023.

- ^ "Archived Pages". Newseum. Archived from the original on June 21, 2008. Retrieved June 22, 2008.

- ^ "Mizzou: The Magazine of the Mizzou Alumni Association, Winter 2009". University of Missouri Alumni Association. Archived from the original on December 23, 2008. Retrieved November 18, 2008.

- ^ Lebovich, William (March 9, 2008). "Newseum by Polshek". ArchitectureWeek. Archived from the original on September 2, 2017. Retrieved March 4, 2010.

- ^ Venkataraman, Nitya (April 10, 2008). "New Museum Tells Media Story". ABC News. Retrieved March 4, 2010.

- ^ Knox, Merrill (May 21, 2013). "ABC's 'This Week' Moving Out of the Newseum, Al Jazeera America Moving In". AdWeek. Archived from the original on October 7, 2014. Retrieved January 29, 2018.

- ^ Chappell, Carisa. "The Inside Scoop on The Newseum Residences". Dc.urbanturf.com. Retrieved January 18, 2013.

- ^ Alan Rusbridger (April 2, 2008). "Washington DC's Newseum opens its doors". The Guardian.

- ^ Landauer, Michael (July 3, 2010). "The power of Washington, D.C., is in its stories, not inside its buildings". Dallas Morning News. Archived from the original on July 6, 2010.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: bot: original URL status unknown (link) - ^ Wach, Bonnie (July 4, 2010). "D.C. in the Digital Age". San Francisco Chronicle.

- ^ Ourousoff, Nicolai (April 11, 2008). "Get Me Rewrite: A New Monument to Press Freedom". The New York Times.

- ^ Rothstein, Edward (April 11, 2008). "Chasing the News: Mark Twain's Inkwell to Blogger's Slippers". The New York Times. p. 1.

- ^ Puente, Maria (April 3, 2008). "Massive Newseum opens window on journalism". USA Today.

- ^ Bowman, James (April 11, 2008). "Media Monument". National Review Online. Archived from the original on June 12, 2008. Retrieved January 4, 2010.

- ^ Moeller, G. Martin (2012). AIA Guide to the Architecture of Washington DC (5th ed.). Baltimore: Johns Hopkins University Press. p. 102. ISBN 978-1-4214-0269-7.

- ^ Schwarz, Jonathan (April 14, 2008). ""Bias" At The New Newseum". Mother Jones.

- ^ Williamson, Kevin D. (April 16, 2008). "Newseum's Bias Discussion". National Review Online. Archived from the original on January 29, 2010. Retrieved January 4, 2010.

- ^ Jack Shafer (October 8, 2009). "The Newseum's Tim Russert Shrine". Slate.

- ^ "Spotlight On Al Aqsa Television". Anti-Defamation League. Archived from the original on August 16, 2013. Retrieved May 13, 2013.

- ^ "Journalists Memorial". Newseum. Retrieved February 2, 2015.

- ^ "Using War as Cover to Target Journalists", By David Carr, New York Times, November 25, 2012

- ^ "One man’s terrorist, another man’s freedom fighter – or journalist", by Ilene Prusher, Haaretz, May 17, 2013

- ^ David Carr Defends Slain Journalists Claim; Israeli accounts challenged the Times columnist’s criticism of Israel for strikes that killed two men he described as journalists. Buzzfeed, November 26, 2012

- ^ "The New York Times–Ochs-Sulzberger Family Great Hall of News". The Newseum.

- ^ Rothstein, Edward (April 11, 2008). "Chasing the News: Mark Twain's Inkwell to Blogger's Slippers". The New York Times. Retrieved November 14, 2010.

- ^ "9/11 Gallery Sponsored by Comcast". The Newseum.

- ^ "Pulitzer Prize Photographs Gallery". The Newseum.

- ^ "Berlin Wall Gallery". The Newseum.

- ^ "Cox Enterprises First Amendment Gallery". The Newseum.

- ^ a b "Journalists Memorial". The Newseum. Retrieved November 14, 2010.

- ^ "Review of Newseum". Frommers.com/Wiley Publishing, Inc. Retrieved November 14, 2010.

- ^ "Tickets | Newseum". www.newseum.org. Retrieved May 31, 2016.

- ^ a b McGlone, Peggy; Roig-Franzia, Manuel (February 9, 2018). "'A slow-motion disaster': Journalism museum in talks about possible building sale". The Washington Post. Archived from the original on February 8, 2018. Retrieved February 9, 2018.

- ^ a b Anderson, Nick; McGlone, Peggy (January 25, 2019). "Johns Hopkins to buy Newseum building in D.C. as journalism museum plans to relocate". The Washington Post. Archived from the original on February 3, 2019. Retrieved February 3, 2019.

- ^ "Form 990: Return of Organization Exempt From Income Tax, 2013: Newseum, Inc" (PDF). CitizenAudit.org. Retrieved February 3, 2019.

- ^ Parker, Lonnae O'Neal; Boyle, Katherine (November 14, 2013). "Can Ron Burgundy save the Newseum?". The Washington Post. Archived from the original on November 15, 2013. Retrieved August 28, 2016.

- ^ Brothers, John (July 9, 2013). "Newseum, Like Many Museums, Unable to Move Beyond the Economic Crisis". Nonprofit Quarterly. Retrieved August 28, 2016.

- ^ Mullin, Benjamin (November 5, 2014). "Newseum CEO James Duff leaves". The Poynter Institute. Retrieved August 28, 2016.

- ^ "2015 990 Tax Return" (PDF). www.guidestar.org. Retrieved June 10, 2017.

- ^ McGlone, Peggy; Brittain, Amy (July 1, 2015). "Heavily in debt, Newseum considered risky strategy to improve finances". The Washington Post. Archived from the original on July 7, 2015. Retrieved August 28, 2016.

- ^ Sullivan, Margaret (August 28, 2017). "Newseum's president steps down as financial review begins". The Washington Post. Archived from the original on August 29, 2017. Retrieved August 28, 2017.

- ^ "Uncertain future for journalism's monument to itself as Newseum's DC building sold". Washington Examiner. January 26, 2019. Retrieved April 22, 2019.

- ^ McGlone, Peggy; Roig-Franzia, Manuel (February 1, 2019). "The Newseum was a grand tribute to the power of journalism. Here's how it failed". The Washington Post. Archived from the original on February 2, 2019. Retrieved February 3, 2019.

- ^ McGlone, Peggy (July 12, 2019). "Newseum's distinctive First Amendment facade will be removed in Johns Hopkins redesign". The Washington Post. Archived from the original on July 13, 2019. Retrieved July 14, 2019.

- ^ Gershon, Livia (March 19, 2021). "The Newseum's Iconic First Amendment Tablet Is Headed to Philadelphia". Smithsonian Magazine. Retrieved May 21, 2021.

- ^ Tanenbaum, Michael (March 18, 2021). "50-ton First Amendment tablet to find new home at Philly's National Constitution Center". PhillyVoice. Retrieved May 21, 2021.

- ^ "Former Newseum almost ready for Johns Hopkins graduate students". September 9, 2022. Retrieved August 27, 2023.

- ^ Roberts, Jessica; Maksl, Adam (2021). Attacks on the American Press: A Documentary and Reference Guide. Santa Barbara: ABC-CLIO. p. 167. ISBN 9781440872570. Retrieved August 5, 2023. This source is an annotated source book intended for use in introductory journalism courses.

- ^ Mullins, Luke (May 4, 2023). "A Memorial to Fallen Journalists Is One Step Closer to Happening on the National Mall". Washingtonian. Retrieved August 5, 2023.

External links

[edit]- Newseum.org at the Wayback Machine (archived December 31, 2019)

- History museums in Washington, D.C.

- Defunct museums in Washington, D.C.

- Journalism

- Mass media museums in the United States

- Museums established in 1997

- Museums disestablished in 2019

- Telecommunications museums in the United States

- 2008 establishments in Washington, D.C.

- 2019 disestablishments in Washington, D.C.

- Penn Quarter

- Pennsylvania Avenue