Kauai

This article needs to be updated. (April 2024) |

Nickname: The Garden Isle | |

|---|---|

March 2003 satellite photo | |

Location in Hawaiʻi | |

| Geography | |

| Coordinates | 22°04′12″N 159°29′51″W / 22.07000°N 159.49750°W |

| Area | 562.3 sq mi (1,456 km2) |

| Area rank | 4th largest Hawaiian Island |

| Highest elevation | 5,243 ft (1598.1 m) |

| Highest point | Kawaikini |

| Administration | |

United States | |

| Symbols | |

| Flower | Mokihana (Melicope anisata)[1] |

| Color | Poni (Purple) |

| Largest settlement | Kapaʻa |

| Demographics | |

| Demonym | Kauaian |

| Population | 73,298 (2020[2]) |

| Pop. density | 118/sq mi (45.6/km2) |

Kauaʻi (Hawaiian: [kɐwˈwɐʔi]), anglicized as Kauai[a] (English: /ˈkaʊaɪ/ KOW-eye[3] or /kɑːˈwɑː.iː/ kah-WAH-ee),[4] is one of the main Hawaiian Islands.

It has an area of 562.3 square miles (1,456.4 km2), making it the fourth-largest of the islands and the 21st-largest island in the United States.[5] Kauaʻi lies 73 miles (117 km) northwest of Oʻahu, across the Kauaʻi Channel. The island's 2020 population was 73,298.[6]

Styling itself the "Garden Isle", Kauaʻi is the site of Waimea Canyon State Park and Na Pali Coast State Park. It forms the bulk of Kauai County, which also includes the small nearby islands of Kaʻula, Lehua, and Niʻihau.

Etymology and language

[edit]Hawaiian narrative derives the name's origin from the legend of Hawaiʻiloa, the Polynesian navigator credited with discovering the Hawaiian Islands. The story relates that he named the island after a favorite son; a possible translation of Kauaʻi is "place around the neck", describing how a father would carry his child. Another possible translation is "food season".[7]

Kauaʻi was known for its distinct dialect of the Hawaiian language, which still survives on Niʻihau. While the dominant dialect is based on that of Hawaiʻi island, which has no [t] sound, the Kauaʻi dialect had this sound. This happened because the Kauaʻi dialect had retained the old Polynesian /t/ sound, replaced in the "standard" Hawaiʻi dialect by [k]. This difference applies to all words with these sounds, so the Kauaian name for Kauaʻi was pronounced "Tauaʻi", and Kapaʻa was pronounced "Tapaʻa".

History

[edit]It is uncertain when humans discovered the Hawaiian islands. Early archaeological studies suggested that Polynesian explorers from the Marquesas Islands or Society Islands may have arrived as early as 600 C.E.,[8] possibly with a second wave arriving from Tahiti around 1100 CE.[9][10] Later analyses suggest that the first settlers arrived around 900–1200 C.E.[11]

In 1778, Captain James Cook arrived at Waimea, Kauai and became the first recorded contact between any European and the indigenous people of the Hawaiian Islands.[12] At the time of Cook’s visit, the Hawaiian islands were divided into several kingdoms.[13]: 30

Kamehameha I established the Kingdom of Hawaii in 1795, uniting most of the Hawaiian islands, but Kauai remained independent. Kamehameha tried to conquer Kauai in 1796 but stormy seas caused the attack from Oahu to be canceled and he was afterward distracted by events elsewhere. By 1803, Kauai was ruled by Kaumualiʻi, who refused to yield his independence. A second invasion of Kauai from Oahu was planned but this too was canceled after an epidemic broke out among Kamehameha's forces. In 1810, a diplomatic agreement was reached whereby Kaumualiʻi agreed to be Kamehameha's vassal and for Kauai to be a tributary kingdom.[13]: 47-50 Kaumualiʻi also ceded Kauai to the Kingdom of Hawaiʻi upon his death in 1824.[citation needed]

Schäffer affair

[edit]The Schäffer affair was a diplomatic episode instigated in 1815 by Georg Anton Schäffer, a German working with the Russian American Company. While at Kauai in 1816, Schaeffer involved Kaumualiʻi in “a treasonable design” whereby Kauai would accept the protection of the Russian Empire in exchange for exclusive trading privileges. In 1817, a fort was built at Waimea and a Russian flag raised over it. But under orders from Kamehameha, and persuaded by other foreign traders, Kaumualiʻi abandoned his relationship with Schaeffer and ordered the Russians to leave Kauai by force.[13]: 57-58

Plantations

[edit]From the 1830s till the mid-20th century, plantations of sugarcane were Kauaʻi's most important industry. In 1835, the first sugarcane plantation was founded on Kauaʻi, and for the next century the industry dominated Hawaiʻi's economy.[14] Kauaʻi's last sugarcane plantation, the 118-year-old Gay & Robinson Plantation, stopped planting sugar in 2008.[15]

Old Sugar Mill of Koloa

[edit]In 1835, Old Koloa Town opened a sugar mill.[16] From 1906 to 1934 the office of County Clerk was held by John Mahiʻai Kāneakua, who had been active in attempts to restore Queen Liliuokalani to the throne after the U.S. takeover of Hawaiʻi in 1893.[17]

Valdemar Knudsen

[edit]Valdemar Emil Knudsen was a Norwegian who arrived on Kauai in 1857. Knudsen, or "Kanuka", originally managed Grove Farm in Koloa. He later sought a warmer land and purchased the leases to Mana and Kekaha, where he became a successful sugarcane plantation owner. He settled in Waiawa, between Mana and Kekaha, immediately across the channel from Niʻihau Island.[18] His son, Eric Alfred Knudsen, was born in Waiawa.

Knudsen was appointed land administrator by King Kamehameha for an area covering 400 km2, and was given the title konohiki as well as a position as a noble under the king. Knudsen, who spoke fluent Hawaiian, later became an elected representative and an influential politician.[19]

Knudsen lends his name to the Knudsen Gap, a narrow pass between Hã’upu Ridge and the Kahili Ridge. Its primary function was as a sugar farm.[20][21]

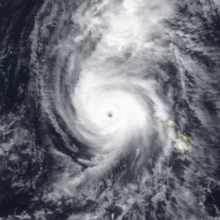

Hurricane Iniki

[edit]

Mark Zuckerberg

[edit]

Geography

[edit]

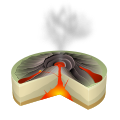

The five-million-year-old island, the oldest of the main islands (Niʻihau is older), was formed volcanically as the Pacific Plate passed over the Hawaii hotspot.[26] It consists of an eroded shield volcano with a 9.3–12.4 mi (15.0–20.0 km) diameter summit caldera and two flanking calderas. Rejuvenation of the volcano 0.6–1.40 million years ago left lava flows and cones over the eastern two-thirds of the island.[27]

Kauaʻi's highest peak is Kawaikini, at 5,243 ft (1,598 m).[28] The second-highest is Mount Waiʻaleʻale, near the center of the island, 5,148 ft (1,569 m) above sea level. One of the wettest spots on earth, with an annual average rainfall of 460 in (38.3 ft; 11.7 m), is on the east side of Mount Waiʻaleʻale. The rain has eroded deep valleys in the central mountains, carving out canyons with many scenic waterfalls. On the west side of the island, Waimea town is at the mouth of the Waimea River, whose flow formed Waimea Canyon, one of the world's most scenic canyons, which is part of Waimea Canyon State Park. At three thousand ft (910 m) deep, Waimea Canyon is often called "The Grand Canyon of the Pacific". Kokeo Point lies on the island's south side.[citation needed] The Na Pali Coast is an isolated center for recreation, including kayaking along the beaches and hiking on the trail along the coastal cliffs.[29] The headlands Kamala Point, Kawai Point, Kawelikoa Point, Kuahonu Point, Paoʻa Point, and Molehu Point are on the southeast of the island; Makaokahaʻi Point and Weli Point are in the south.

Climate

[edit]| Kauaʻi | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Climate chart (explanation) | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

Kauaʻi's climate is tropical, with generally humid and stable conditions year-round, although infrequent storms cause severe flooding. At the lower elevations, the annual precipitation varies from an average of about 50 in (130 cm) on the windward (northeastern) shore to less than 20 in (51 cm) on the (southwestern) leeward side of the island. The average temperature in Lihu'e, the county seat, ranges from 78 °F (26 °C) in February to 85 °F (29 °C) in August and September.

Kauaʻi's mountainous regions offer cooler temperatures in contrast to the warm coastal areas. At Kōkeʻe State Park, 3,200–4,200 ft (980–1,280 m) ASL, day temperatures vary from an average of 45 °F (7 °C) in January to 68 °F (20 °C) in July. In the winter, temperatures have been known to drop down to the 30s and 40s at the park, which holds an unofficial record low of 29 °F (−2 °C), recorded in February 1986 at Kanaloahuluhulu Meadow.

Precipitation in Kauaʻi's mountainous regions averages 50–100 in (1,300–2,500 mm) annually. About ten mi (16 km) southeast of Kōkeʻe state park, at an elevation of 5,075 ft (1,547 m), is the Mt. Waiʻaleʻale rain gauge.[31] Mt. Waiʻaleʻale is often cited as the wettest spot on earth, although this has been disputed. Based on data for the period from 1931 through 1960, the average yearly precipitation was 460 in (11,700 mm) (U.S. Environmental Science Services Administration, 1968). Between 1949 and 2004, the average yearly precipitation at Mt. Waiʻaleʻale was 374 in (9,500 mm).[32]

Kauaʻi also holds a record in hourly precipitation. During a storm on January 24–25, 1956, a rain gauge at Kauaʻi's former Kilauea Sugar Plantation recorded a record twelve in (305 mm) of precipitation in just 60 minutes. The value for one hour is an underestimate, since the rain gauge overflowed, which may have resulted in an error by as much as 1 in (25 mm).[33] An accurate measurement may have exceeded Holt, Missouri's world-record rainfall of 12 in (300 mm) in 42 minutes on June 22, 1947.[34]

Time zone

[edit]Hawaii Standard Time (UTC−10:00) is observed on Kauaʻi year-round. When mainland states are on daylight saving time, for example, the time on Kauaʻi is three hours behind the West Coast of the United States and six hours behind the East Coast.[35]

River system

[edit]- Waimea River 35.7 km (22.2 mi)

- Hanalei River 26.5 km (16.5 mi)

- Hanapēpē River 24.2 km (15.0 mi)

- Wainiha River 24 km (15 mi)

- Wailua River 23.4 km (14.5 mi)

- Makaweli River 23.2 km (14.4 mi)

- Huleia River 21.4 km (13.3 mi)

- Kalihiwai River 20 km (12 mi)

- Anahola River 19.4 km (12.1 mi)

- Lumahaʻi River 16 km (9.9 mi)

- Kōʻula River 14.8 km (9.2 mi)

- Olokele River 14.4 km (8.9 mi)

- Kilauea Stream 13.4 km (8.3 mi)

- Waikomo Stream 9.8 km (6.1 mi)

Waterfalls

[edit]- Halii Falls

- Hanakapiai Falls

- Hinalele Falls

- Kalihiwai Falls

- Kilauea Falls

- Manawaiopuna Falls

- Opaekaa Falls

- Waialae Falls

- Wailua Falls

- Waipoo Falls

-

Waipoo Falls at Waimea Canyon State Park

Economy

[edit]Tourism is Kauaʻi's largest industry. In 2007, 1,271,000 people visited. The two largest groups were from the continental United States (84% of all visitors) and Japan (3%).[36] As of 2003, approximately 27,000 jobs existed on Kauaʻi. The largest sector was accommodation/food services (26%, 6,800 jobs), followed by government (15%) and retail (14.5%), with agriculture accounting for 2.9% (780 jobs) and educational services providing 0.7% (183 jobs).[37] The visitors' industry accounted for one third of Kauaʻi's income.[37] Employment is dominated by small businesses, with 87% of all non-farm businesses having fewer than 20 employees.[37] As of 2003, Kauaʻi's poverty rate was 10.5%, compared to the mainland at 10.7%.[37]

As of 2014, the median home price was about $400,000.

Land in Kauaʻi is very fertile; farmers raise many varieties of fruit and other crops. Guava, coffee, sugarcane, mango, banana, papaya, avocado, star fruit, kava, noni and pineapple are all cultivated on the island, but most agricultural land is used for raising cattle.[36]

Kauaʻi is home to the U.S. Navy's "Barking Sands" Pacific Missile Range Facility, on the western shore.

MF and HF ("shortwave") radio station WWVH, sister station to WWV and low frequency WWVB in Fort Collins, Colorado, is on the west coast of Kauaʻi, about 3 mi (5 km) south of Barking Sands. WWVH, WWV and WWVB are operated by the US National Institute of Standards and Technology, broadcasting standard time and frequency information to the public.

Energy

[edit]Kauaʻi Island Utility Cooperative (KIUC) is a not-for-profit electric utility cooperative headquartered in Līhuʻe, which provides electricity for the island. It has 24,000 member-owners who elect a nine-member board of directors.[38]

In the 1970s, Kauaʻi burned sugarcane waste to supply most[39] of its electricity.[39]

By 2008, transition of energy sources and growth in generating capacity had occurred, with most of Kauaʻi's electricity produced by imported liquid petroleum. In 2006 and 2007, the inputs cost $69.3 million and $83 million, respectively.[40] By 2011, 92% of KIUC's power came from diesel.[41]

By 2017, KIUC's fuel mix was 56% fossil fuels, 9% hydroelectric, 12% biomass and 23% solar. KIUC integrated large-scale solar into its grid so that, during sunny daylight hours, 97% or more of its generation came from renewable sources. KIUC offers $1,000 rebates to residential customers who have solar water heating systems installed on their homes.[42]

In 2017, KIUC opened a Tesla Energy 13 MW / 52 MWh battery next to the 12 MW Kapaia solar plant[43] for 13.9¢/kWh.[41] In December 2018, KIUC opened an AES Distributed Energy project for 20 MW solar with 20 MW / 100 MWh batteries priced at 11.1¢/kWh.[44]

Towns and communities

[edit]Līhuʻe, on the island's southeastern coast, is the seat of Kauaʻi County and the island's second-largest town. Kapaʻa, on the "Coconut Coast" (site of an old coconut plantation) about 6 mi (9.7 km) north of Līhuʻe, has a population of over 10,000, or about 50% greater than Līhuʻe. Princeville, on the island's north side, was once the capital of Kauaʻi.

Communities on Kauaʻi range in population from the roughly 10,000 people in Kapaʻa to tiny hamlets. Below are the larger or more notable of those from the northernmost end of Hawaii Route 560 to the western terminus of Hawaii Route 50:[citation needed]

| Name | population |

|---|---|

| Haʻena State Park | 550 |

| Wainiha | 419 |

| Hanalei | 450 |

| Princeville | 2,158 |

| Kalihiwai | 428 |

| Kilauea | 3,014 |

| Anahola | 2,311 |

| Kapaʻa | 11,652 |

| Wailua | 2,359 |

| Hanamāʻulu | 4,994 |

| Līhuʻe | 8,004 |

| Wailua Homesteads | 5,863 |

| Puhi | 3,380 |

| Poʻipū | 1,299 |

| Kōloa | 2,231 |

| Lāwaʻi | 2,578 |

| Kalāheo | 4,996 |

| ʻEleʻele | 2,515 |

| Hanapēpe | 2,678 |

| Kaumakani | 749 |

| Waimea | 2,057 |

| Kekaha | 3,715 |

| Pakala | 294 |

| Kealia | 103 |

-

Hanalei town with a view of Mt. Na Molokama, and Māmalahoa

-

Northeastern coast of Kauaʻi, near Kīlauea

-

View of the Pacific Ocean, from the island's south shore

-

Anahola Bay is a snorkeling and swimming beach with clear pools and a long coral reef

Transport

[edit]Air

[edit]

Located on the southeastern side of the island, Lihue Airport is the island's only commercial airport. It has direct routes to Honolulu, Kahului/Maui, Kona/Hawaii, the U.S. mainland, and Vancouver, Canada. General aviation airports on the island are Port Allen Airport and Princeville Airport. The Pacific Missile Range Facility has a 6,006-foot runway that is closed to general aviation traffic, but could be used for an emergency landing.

Highways

[edit]Several state highways serve Kauaʻi County:

- Hawaii Route 50, also known as Kaumualiʻi Highway, is a thirty-three mile road that stretches from Hawaii Route 56 at the junction of Rice Street in Līhuʻe to a point approximately 1/5 mile north of the northernmost entrance of the Pacific Missile Range Facility on the far western shore.

- Hawaii Route 58 stretches 2 mi (3.2 km) from Route 50 in Līhuʻe to the junction of Wapaa Road with Hawaii 51 near Nawiliwili Harbor on Kauaʻi.

- Hawaii Route 56, also known as Kuhio Highway, runs 28 mi (45 km) from Hawaii Route 50 at the junction of Rice Street in Līhuʻe to the junction of Hawaiʻi Route 560 in Princeville.

- Hawaii Route 560 passes 10 mi (16 km) from the junction of Route 56 in Princeville and dead ends at Keʻe Beach in Haʻena State Park.

Other major highways that link other parts of the Island to the main highways of Kauaʻi are:

- Hawaii Route 55 covers 7.6 mi (12.2 km) from the junction of Route 50 in Kekaha to meet with Hawaii Route 550 south of Kokeʻe State Park in the Waimea Canyon.

- Hawaii Route 550 spans 15 mi (24 km) from Route 50 in Waimea to Kōkeʻe State Park.

- Hawaii Route 540 goes 4 mi (6.4 km) from Route 50 in Kalaheo to Route 50 in Eleʻele. The road is mainly an access to residential areas and Kauaʻi Coffee. It also functions as a bypass between Kalaheo and ʻEleʻele.

- Hawaii Route 530, also called Kōloa Road, stretches 3.4 mi (5.5 km) from Route 50 between Kalaheo and Lawai to Route 520 in Koloa. The road is mainly an alternative to Route 520 for travel from the west side to Poʻipū.

- Hawaii Route 520 runs 5 mi (8.0 km) from the "Tunnel of Trees" at Route 50 to Poʻipū on the south shore.

- Hawaii Route 570 covers 1 mi (1.6 km) from Route 56 in Līhuʻe to Līhuʻe Airport.

- Hawaii Route 580 spans 5 mi (8.0 km) from Route 56 in Wailua to where the road is no longer serviced just south of the Wailua Reservoir.

- Hawaii Route 581 passes 5 mi (8.0 km) from Route 580 in the Wailua Homesteads to a roundabout just west of Kapaʻa Town.

- Hawaii Route 583, also known as Maalo Road, stretches 3.9 mi (6.3 km) from Route 56 just north of Līhuʻe to dead-end at Wailua Falls Overlook in the interior.

Hawaii Scenic Byway

[edit]- Holo Holo Koloa Scenic Byway, this state designated scenic byway runs over 19 mi (31 km) and connects many of Kauaʻi's most historical and cultural sights such as the Maluhia Road (Tree Tunnel), Puhi (Spouting Horn), The National Tropical Botanical Gardens, and the Salt Beds.

Mass transit

[edit]The Kauaʻi Bus is the public transportation service of the County of Kauaʻi.

Places of interest

[edit]

The Kauaʻi Heritage Center of Hawaiʻian Culture and the Arts was founded in 1998. Its mission is to nurture appreciation and respect for Hawaiian culture. It offers classes in Hawaiian language, hula, lei and cordage making, the lunar calendar, chanting, and trips to cultural sites.

- Alakai Wilderness Area

- Allerton Garden

- Camp Naue YMCA

- Fern Grotto

- Haʻena State Park

- Hanalei Bay

- Hoʻopiʻi Falls

- Honopū Valley

- Kōkeʻe State Park

- Limahuli Garden and Preserve

- Makaleha Mountains

- Makauwahi Cave Reserve

- McBryde Garden

- Moir Gardens

- Moloaa Bay

- Na ʻĀina Kai Botanical Gardens

- Nā Pali Coast State Park

- ʻOpaekaʻa Falls

- Paoʻa Point

- Poipu Beach Park

- Polihale State Park

- Queen's Bath

- Sleeping Giant (Nounou Mountain)

- Spouting Horn

- Wailua River

- Waimea Canyon State Park

Panorama gallery

[edit]Popular culture

[edit]

Kauaʻi has been featured in more than 70 Hollywood movies and TV shows, including the musical South Pacific and Disney's 2002 animated feature film Lilo & Stitch along with its franchise's three sequel films (2003's Stitch! The Movie, 2005's Lilo & Stitch 2: Stitch Has a Glitch, and 2006's Leroy & Stitch) and first television series (Lilo & Stitch: The Series). Scenes from South Pacific were filmed in the vicinity of Hanalei. Waimea Canyon was used in the filming of the 1993 film Jurassic Park and its 2015 sequel Jurassic World was shot in Kauai. Scenes by a waterfall in Mighty Joe Young were shot in Kauai. Parts of the island were used for the opening scenes of the film Raiders of the Lost Ark. Other movies filmed here include Six Days Seven Nights, the 1976 King Kong,[45] and John Ford's 1963 film Donovan's Reef. Recent films include Tropic Thunder and a biopic of Bethany Hamilton, Soul Surfer. A scene in the opening credits of popular TV show M*A*S*H was filmed in Kauaʻi (helicopter flying over mountain top). Some scenes from Just Go with It, George of the Jungle, and Pirates of the Caribbean: On Stranger Tides were also filmed in Kauaʻi.[46] A Perfect Getaway is set in Kauaʻi.

Parts of the 2002 film Dragonfly were filmed in 2001 in Kauai,[47] but the people and the land were presented as South American.[citation needed]

Major acts of two Elvis Presley films, 1961's Blue Hawaii and 1966's Paradise, Hawaiian Style, were filmed on Kauaʻi. Both have scenes shot at the Coco Palms resort.

The Descendants, a 2011 film, has major parts shot in Kauaʻi, where the main character and his cousins own ancestral lands they are considering selling.[48] The film is based on the 2007 novel by Hawaiian writer Kaui Hart Hemmings.

See also

[edit]Explanatory notes

[edit]- ^ In Hawaiian there is a glottal stop before the final i, spelled with the ʻokina. English speakers may approximate this by pronouncing the name as /kɑːˈwɑːiː/ kow-AH-ee. Sometimes Kauaʻi is spelled with an apostrophe or grave accent rather than the ʻokina, as in Kaua'i or Kaua`i.

References

[edit]- ^ "Mokihana". Native Hawaiian Plants. Kapiʻolani Community College. Archived from the original on March 23, 2009. Retrieved March 7, 2009.

- ^ "U.S. Census Bureau QuickFacts: Kauai County, Hawaii". United States Census Bureau. April 1, 2020.

- ^ "Kauai". Dictionary.com Unabridged (Online). n.d.

- ^ "Kauai". Merriam-Webster.com Dictionary. Merriam-Webster.

- ^ "Table 5.08 – Land Area of Islands: 2000" (PDF). 2004 State of Hawaii Data Book. State of Hawaii. 2004. Archived (PDF) from the original on March 9, 2013. Retrieved July 23, 2007.

- ^ Census Tracts 401 through 409, Kauaʻi County United States Census Bureau

- ^ Pukui, Mary Kawena; Elbert, Samuel H.; Mookini, Esther T. (1974). Place Names of Hawaii. University of Hawaii Press. ISBN 978-0-8248-0524-1.

- ^ "Late Quaternary Chronology and Stratigraphy of Twelve Sites On Kaua'i".

- ^ "Kauai's History". Kauai.com. Archived from the original on June 10, 2021. Retrieved June 10, 2021.

- ^ "Kauai in History: Hawaii's Oldest Paradise". Makana Charters and Tours. Makana Charters. March 3, 2020. Archived from the original on June 10, 2021. Retrieved June 10, 2021.

- ^ Kirch, Patrick (2011). "When did the Polynesians Settle Hawaii? A review of 150 years of scholarly inquiry". Hawaiian Archaeology. 12: 3–27.

- ^ Hough, Richard (1997). Captain James Cook: a biography. New York: Norton. p. 311. ISBN 978-0-393-31519-6.

- ^ a b c Kuykendall, Ralph S. (1938). The Hawaiian Kingdom 1778-1854 Vol 1 Foundation and Transformation. Honolulu: University of Hawaii Press.

- ^ "Kauai Plantation Railway – Kauai Sugarcane Plantations". Archived from the original on March 29, 2014. Retrieved May 8, 2011.

- ^ "About Gay and Robinson in Hawaii". www.hawaiiforvisitors.com. Retrieved April 18, 2024.

- ^ "Kauai History". Hawaiian Tourism Authority. Archived from the original on July 19, 2013. Retrieved June 16, 2012.

- ^ Soboleski, Hank (August 10, 2013). "John Mahiai Kaneakua". The Garden Island. Archived from the original on January 23, 2014. Retrieved January 15, 2014.

- ^ Joesting, Edward (1988). Kauai: The Separate Kingdom. University of Hawaii Press. Pages 198–199. ISBN 9780824811624.

- ^ Lund, Fredrik Larsen (2017). Norske utposter. Vega forlag. Pages 301–302. ISBN 978-82-8211-537-7.

- ^ Lougheed, Vivien (2007). Adventure Guide: Mazatalan and Vicinity. Hunter Publishing, Inc. Page 250. ISBN 9781588435910.

- ^ Ward, Greg (2002). Hawaii. Rough Guides. Page 472. ISBN 9781858287386.

- ^ Central Pacific Hurricane Center (1993). The 1992 Central Pacific Tropical Cyclone Season (PDF) (Report). National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration. Retrieved November 24, 2003.

- ^ a b "Hawaiians call Mark Zuckerberg 'the face of neocolonialism' over land lawsuits". The Guardian. January 23, 2017. Archived from the original on April 4, 2022. Retrieved April 4, 2022.

- ^ Mark Zuckerberg hits back at 'misleading' claims he is suing Hawaiian landowners Archived November 10, 2017, at the Wayback Machine, Wired, January 20, 2017

- ^ "Facebook's Zuckerberg officially drops Hawaii 'quiet title' actions" Archived March 4, 2017, at the Wayback Machine, Pacific Business News, February 26, 2017

- ^ Juvik, Sonia P.; Juvik, James O.; Paradise, Thomas R. (1998). Atlas of Hawai'i. University of Hawaii Press. pp. 3–6. ISBN 978-0-8248-2125-8.

- ^ "Kauai". Global Volcanism Program. Smithsonian Institution. Retrieved June 28, 2021.

- ^ "Table 5.11 – Elevations of Major Summits" (PDF). 2004 State of Hawaii Data Book. State of Hawaii. 2004. Archived (PDF) from the original on March 9, 2013. Retrieved July 23, 2007.

- ^ "Trail Information – Kalalau Trail". Archived from the original on August 30, 2011. Retrieved September 7, 2011.

- ^ "NASA Earth Observations Data Set Index". NASA. Archived from the original on November 28, 2017. Retrieved January 30, 2016.

- ^ Henning, D. (1967). Mt. Waialeale. Wetter und Leben (Vienna). 19(5–6), 93–100

- ^ USGS, NWIS

- ^ Schmidli, R.J. (1983). Weather extremes (NOAA Technical Memorandum NWS WR-28, Revised.) Salt Lake City, UT: NOAA.

- ^ National Climatic Data Center

- ^ "Discover Kauai". H&S Publishing, LLC. Archived from the original on February 13, 2011. Retrieved April 2, 2011.

- ^ a b "Kauai Economic Outlook Summary: Tourism Woes Mean No Growth Through 2009". University of Hawaii Economic Research Organization. 2008. Archived from the original on September 27, 2008. Retrieved November 5, 2008.

- ^ a b c d "Kauai Economic Development Plan 2005–2015" (PDF). County of Kauai Office of Economic Development, Kauai Economic Development Board. 2004. Archived (PDF) from the original on December 18, 2008. Retrieved November 5, 2008.

- ^ "Home | Kauai Island Utility Cooperative". website.kiuc.coop. Archived from the original on June 17, 2021. Retrieved June 10, 2021.

- ^ a b "Hawaii's sugar growers are putting new emphasis on their..." United Press International. Archived from the original on July 29, 2021. Retrieved July 29, 2021.

- ^ Flynn, Meghan. Kauai Island Utility Cooperative. Energy Today Magazine. September 30, 2008

- ^ a b Wagman, David (March 16, 2017). "Tesla Teams With Tiny Hawaiian Utility to Store Solar". IEEE. Archived from the original on March 30, 2017. Retrieved March 29, 2017.

as 2011 we were 92% dependent on fossil fuel generation," primarily diesel and naphtha.

- ^ "Residential Heat Pump Water Heater Rebate" (PDF). Kaua'i Island Utility Cooperative. Archived (PDF) from the original on July 29, 2021. Retrieved July 29, 2021.

- ^ "Tesla launches its Powerpack 2 project in Hawaii, will help Island of Kauai get more out of its solar power". March 8, 2017. Archived from the original on March 8, 2017. Retrieved March 8, 2017.

- ^ "AES' New Kauai Solar-Storage 'Peaker' Shows How Fast Battery Costs Are Falling". January 16, 2017. Archived from the original on January 18, 2017. Retrieved January 24, 2017.

- ^ "King Kong (1976) Filming Locations" Archived 2017-03-19 at the Wayback Machine imdb.com

- ^ "Kauai Film Locations | GoHawaii.com". www.gohawaii.com. February 14, 2017. Archived from the original on August 3, 2017. Retrieved August 3, 2017.

- ^ "Feature Films Made Partially or Entirely in Hawaii". filmoffice.hawaii.gov. Retrieved December 15, 2024.

- ^ "Kauai 'Cane Fire' Documentary Will Blow Lid Off Hawaii Tourism". Beat of Hawaii. May 20, 2022. Retrieved May 21, 2022.

Further reading

[edit]- Cook, Chris (1996). The Kauaʻi Movie Book. Landscape photography by David Boynton. Honolulu: Mutual Publishing. ISBN 1-56647-141-9.

- Joesting, Edward (February 1, 1988). Kauai: The Separate Kingdom. University of Hawaii Press. ISBN 978-0-8248-1162-4.

- Sprout, Jerry; Sprout, Janine (November 22, 2016). Kauai Trailblazer: Where to Hike, Snorkel, Bike, Paddle, Surf. Diamond Valley Company. ISBN 978-0-9913690-6-5.